“We Are Here as a Laboratory for Russia’s Future”

The RSCM Congress participants

This little congress, which brought together Russian thinkers, professors, and students — all of whom were forced to leave Russia after the Revolution of 1917 — provided a particular inspiration to its participants and became the foundation of one of the leading Christian movements of the 20th century.

On the 4th and 5th of October, 2023, Saint Philaret’s Institute and the Alexander Solzhenitsyn House of Russia Abroad ran a conference in Moscow, the title rubric of which was “The Russian Student Christian Movement: Experience of Making Life Ecclesial”. The conference brought together participants from across Russia and from abroad, to discuss topics such as the Movement’s experience of church order (structure), the attainment of church unity, the Christian nurturing of young people, as well as the theological findings which came out of the Movement.

Solzhenitsyn House director, DHis Candidate Viktor Moskvin, underscored the role of the RSCM in his introductory word to the gathered attendees, saying “the Russian Student Christian Movement played a very important role, and not only for the Russian church.”

Viktor Moskvin

Current RSCM Chairman, Kirill Sollogub, summarized the Movement’s history for those gathered. He explained how the Movement understood its responsibility for the church and its mission, giving examples of how the RSCM acted within the life of the church from different periods of the Movement’s history.

Kirill Sollogub

SFI First Vice Rector and Chairman of the Transfiguration Fellowship, Dmitry Gasak discussed and compared the ecclesiological meaning of “making life ecclesial” (otserkovlenie) and “coming into the church/being received by the church” (votserkovlenie) by analysing the experiences of helping youth come to unity of faith and life in contemporary Russia, vs. a hundred years ago in the Russian emigration.

Dmitry Gasak

Giovanna Parravicini, a researcher from the Pokrovskie Vorota Cultural Centre, spoke of the experience of “making life ecclesial” (otserkovlenie) amongst catholic movements from the 20th century that provided an alternative to secularism, the “death” of Christian culture, “student uprisings” and the affirmation of left-wing atheistic culture under the influence of Soviet Marxist/Leninist ideology. A rejection of external submission of life to the typical rites and ethical norms by which church life was often characterized, as well as a burning desire to obtain living fellowship with Christ, was common for these сatholic movements, as for similar movements within the Russian 20th c. church (i.e. Mother Maria Skobtsova). This, however, did not mean dissent into subjectivism and individualism: it is no coincidence that even the names of these catholic movements of new type (e.g., С0mmunion and Liberation”, or Fokoljari, which means “hubs” or “meeting places” in Italian) put emphasis on the life in communities.

Giovanna Parravicini

Natalia Likvintseva, a DPhil Candidate and senior researcher at Solzhenitsyn House of Russia Abroad, spoke about the service and thought of one of the leading RSCM activists, Ivan Lagovsky, who was canonized in 2012. Likvintseva recalled his presentations about the state of the church in the USSR, which often morphed into prayer sessions for Russia, and especially his participation in Vasily Zenkovsky’s Study of the Teaching of Religion, for which the Movement was a “laboratory”, of sorts. Lagovsky became one of the developers for Zenkovsky’s somewhat utopian idea of a fully religious school. He wrote that the goal of such a school is “to open and create that force in a person, which organises the integrity (unity) of his life, creating a living and dynamic centre out of which come all his love and hate and within which all manifestations of internal and external life come into holistic and personal creative relationship, are freely chosen or rejected by the person, and distribute themselves hierarchically.” Lagovsky noted that a similar, “integral religious worldview” was used by Soviet schools for the creation of their “antireligious worldview”.

Natalia Likvintseva

Professor at SFI and the Russian State Pedagogical University named after Alexander Gertsen, DPhil Yulia Balakshina, presented the way in which Fr Sergei Bulgakov’s friend, holy martyr Konstantin Ageev, understood what it meant to “make culture ecclesial”. Ageev was an activist at the Local Church Council of 1917–18 and a participant in the “Group of 32” Petersburg zealot-priests standing for renewal of the church life.

Other presentations on the roots of the Movement and its relationship with the YMCA and with church movements in Russia were also made at the conference. These included papers by: Elena Starostenkova, Director of the “101st km Zealots of Maloyaroslavets” Charitable Fund (“Chosen Extracts from Correspondence between RSCM Activists in the 1920’s”); Anna Sakharova, on the activities of Reverend Frederick Charles Meredith in Russia is 1919–20; and Pavel Tribunsky, DHis Candidate and a senior researcher at Solzhenitsyn House of Russia Abroad (“Paul Anderson, Donald Laury and Eastern European Fund Programmes in the 1950s”).

Konstantin Oboznyj, Yulia Balakshina, Anna Sakharova

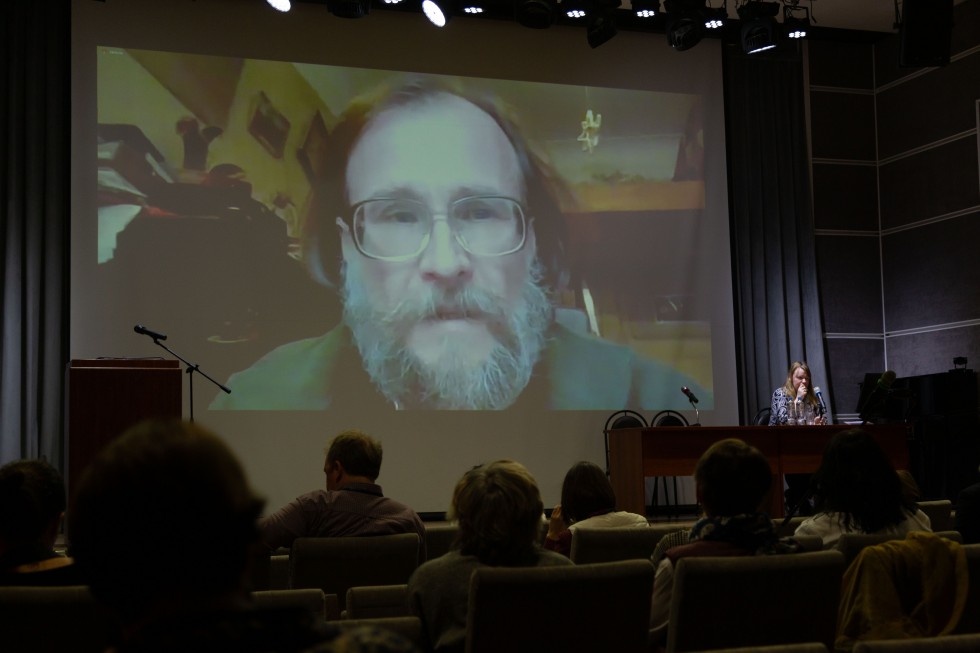

In the conference section on “Paris School” Theology closely connected with RSCM, Viktor Aleksandrov, who is a member of the “RCM Journal” Editorial Board, presented on the early career and coming of age of Nikolay Afanasiev, a student of archpriest Sergei Bulgakov now known for his development of “eucharistic ecclesiology”.

Viktor Aleksandrov (on the screen), Yulia Antipina, Aleksandr Burov, Lyudmila-Ilona Skorobogatova

Lyudmila-Ilona Skorobogatova, an Editor for the SFI Quarterly Journal, spoke of the place Fr Nikolay Afanasiev assigned to Christian organizations when reflecting upon the service of laypeople in the Church.

Lyudmila-Ilona Skorobogatova

Member of the “RCM Journal” Editorial Board and Board of Directors of YMCA-Publishing, Daniel Struve, presented on most important ecclesiological ideas of Fr Sergei Bulgakov, one of the RSCM founders. These ideas are laid down in his articles about the Movement published in the “RCM Journal”.

Post-graduate student and ThM (SFI) Yulia Antipina, from St Petersburg Spiritual Academy, told the conference of Fr Sergei Bulgakov’s ecumenical efforts in relation to the founding of the Fellowship of Rev Sergius and St Alban in London, in 1928. The Fellowship brought together Anglicans and Orthodox Christians. The rejection of an interconfessional approach for organizing the life of the RSCM itself, as well as the choice in favour of delving deeper into the Orthodox tradition, became one of the spiritual factors enabling Fr Sergei to advance in conversation with Christians from other confessions. Fr Sergei was able to take a whole series of bold steps, up to and including regular celebration of the Eucharist together. Antipina drew conclusions on how Fr Sergei viewed prospects for church unity using materials from the Fellowship’s journal “Sobornost”, some of which had never previously been translated into Russian.

Yulia Antipina

In a retrospective presentation, Editor-in-chief of “RCM Journal”, Tatyana Viktorova, shed light on the hundred-year history of the publication which aired the voices of its publishers, authors and readers, including acclaimed voices such as those of Nikolay Zernov, Ivan Lagovsky, Vasily Zenkovsky, Fr Sergei Bulgakov, Nikolay Berdyaev, Nikita Struve, Sergei Averintsev and others. She especially emphasized the role of the Journal in the creation of a single arena for fellowship which knew no national or confessional borders. “Fellowship between Christians from different confessions is a source of different and surprising creative energies that free us from our cultural blind-spots and prejudices,” said Viktorova, quoting the Journal’s first editor, Nikolay Zernov.

“The appearance of the journal was a gift from above,” Fr Georgy Kochetkov said to assembled RSCM members and guests of the roundtable. Fr Georgy is spiritual father of the Transfiguration Fellowship and was himself a reader of the Journal in the 1970s. “Out from inside our Soviet reality, which was so far from that which RSCM and the Journal were doing, it was as if I came into contact with a healthy Russian society, which I imagined to be as it should be.”

Tatyana Viktorova

DPhil Oleg Yermishin, Professor at the Financial University under the Government of the RF, senior researcher of House of Russia Abroad spoke of two different visions for the Movement held by Vasily Zenkovsky and Nikolay Berdyaev. “Berdyaev insisted upon spiritual activity and stressed the importance of the Movement development and presence of social work that could be seen amongst members of other Christian confessions. It goes without saying that he did not simply believe that the Movement, being Orthodox, should just copy what other confessions where doing, but thought the Orthodox should find their own expressions of social work. Zenkovsky believed that ideological indifference was a potential strength, rather than a weakness of the RSCM. He thought that social and political neutrality helped pull people together, assisting unity, and that over-politization was, on the contrary, a disintegrating force. This expresses Zenkovsky’s principle view of the difference between Orthodoxy and western confessions, which sought to actively influence political processes.”

Oleg Yermishin

DPhil Konstantin Antonov, Head of the Philosophy and Religious Studies Department of the Theology Faculty at St. Tikhon's Orthodox University, spoke on Vasily Zenkovsky’s recollections of the first RSCM Congress in Přerov, in his presentation entitled “Vasily Zenkovsky on the first Přerov Congress: Memories or the Psychological Analysis of a Religious Event?”

“Fr Vasily’s recollections about the establishment of the RSCM and the congress at Přerov are not only talented from a literary point of view but are, without question, psychological. Fr Vasily writes as a teacher and a psychologist who’s primary interest is religion,” said Antonov. “His description of the religious feeling and experience of the participants at Přerov was not just a description of individual experiences or their sum, but of something greater — he describes a new reality arising among them, like an ever-increasing electric current.”

Aleksandr Burov, a senior researcher at the State History Museum, spoke of the ideological context of the Movement in the pre-war years and the so-called “third way” it was trying to chart for structuring societal life. This “third way” juxtaposed formal, contemporary democracy, on the one hand, and a godless, tyrannical bolshevism on the other. The activists of the Movement understood Christianity as social and, therefore, sought “social Christianity”.

Aleksandr Burov

The conference also had a separate section focussing on the Movement’s ecclesiological basis at which participants discussed: the RSCM’s experience of sobornost (Ulyana Gunter), the frescos in the chapel of Basil the Great in London, authored by iconographer Joanna Reitlinger, who was a spiritual daughter of Fr Sergei Bulgakov (Maria Patrusheva), and the influence of the RSCM on the life in the church in Soviet and post-Soviet Russia, especially on Fr Aleksandr Men and Fr Georgy Kochetkov (Andrei Dudarev).

In Fr Georgy’s opinion, the question of what kind of influence church movements have upon each other cannot be unequivocally answered. On the one hand, the birth of any community or brotherhood has its roots within the community itself; in this way, also, forms which adequately expressed participants’ spiritual state and consciousness arose amongst activists in the emigration. On the other hand, we cannot discount the enormous role and influence of great theologians and philosophers like Bulgakov and Berdyaev, and many others, on the life of the Transfiguration Fellowship.

Andrei Dudarev, Fr Georgy Kochetkov

The conference section called “Facing Russia: the RSCM in the Soviet Union”, provided a forum for discussing RSCM activities in Soviet Russia and its influence on church life in the Soviet Union.

The section featured presentations on the RSCM’s aid to the faithful in the USSR (Barbara Martin) and its role in shedding light on church life in the Soviet Union in the post-war period (Vitaly Cherkasov) and during Perestroika (Marina Kosukhina). Dean of the SFI Faculty of History, DHis Candidate Konstantin Oboznij, made a presentation on the subsequent fates, later in the 20th century, of several of the founding RSCM members who were present at the Přerov congress.

Konstantin Oboznij

The conference also included a presentation of book by Ulyana Gunter entitled “The Russian Student Christian Movement: sources and roots, inception and activities in 1923–1939” revealing different aspects of RSCM life in emigration.

Ulyana Gunter, Kirill Mozgov

The conference closed with a roundtable discussion, at which participants heard personal testimonies from people involved in RSCM life and activities in France during the second half of the 20th century, and from those whose lives were transformed by the Movement’s activities in Russia and their reading of the RSCM Journal.

The roundtable discussion participants

Konstantin Antonov

Marina Kosukhina

Vitalij Cherkasov

Konstantin Oboznij, Aleksandr Burov

Fr Georgy Kochetkov

The roundtable discussion

The roundtable discussion participants

Elena Starostenkova

The conference participants

Pavel Tribunsky

Anna Sakharova

Daniil Struve (on the screen)

Lidiya Kroshkina

Dmitry Gasak

Andrei Dudarev

The RSCM summer camp participants, 1947