The Eucharist: Pentecost or the Mystical Supper?

Recently, when musing on women’s ministry in the church, I said that women could be elders in the church gathering – and this has, on more than one occasion, been confirmed in history, as far back as the first centuries of the church’s existence. Women could lead church philanthropic ministries or, for instance, educational ministries or mission. And if she were a prophet and found herself in a situation where there were no other elders in a church gathering, or if it were a gathering only of sisters, than she could also bring forth some form of thanksgiving on behalf of the group. In fact, these gifts are given to the entire People of God. Only a woman shouldn’t be any sort of hierarchical figure. These days, when people speak about women’s ordination, they mean bringing women into the hierarchy of the church, where they would become priests and bishops in the modern sense of these words. This is ridiculous. And yet, women really can lead various gatherings of the faithful, although in this position a woman is usually a “scourge from God”. When sisters become elders in the church gathering, especially if there are also brothers who aren’t managing to take the responsibility on themselves – as happens so often in our country in modern times – than these traits of being a “scourge from God” are bound to keep appearing among our women.

In the past, in the history of church, women were able to administer the mysteries of baptism, the distribution of communion, the mystery of the word, the mysteries of love and peace, and of agape. A woman could do all of this, given particular conditions. In the modern church tradition, however, in order to celebrate the mystery of thanksgiving, one requires a canonically approved hierarchical representative. But this isn’t destiny! There were times when the church didn’t have any hierarchical representatives and yet the Eucharist was celebrated. The church never lived without the Eucharist. The Apostles could celebrate the Eucharist, then bishop-priests, just as could prophets and possibly women prophets, who disappeared from the church as a result of the arrival of hierarchical relationships and the birth of hierarchy itself within the church. It is not without reason that a matter of primary fervour for the Montanists, who around 200 AD accused the church of departure from its initial principles, was that Christians were distancing themselves from Evangelistic principles and returning to the ways of the Old Covenant. And this was a fair point: the church really was returning to the Old Covenant, first and foremost in its establishment of hierarchy, at that time – a single rank, and the establishment of self-righteous laws issuing from an incorrect understanding of the words of Christ with regard to the Law, which shouldn’t be broken but “fulfilled” (in the sense of “completion via renewal”).

Rembrandt Harmensz van Rijn. An Old Woman Reading, Probably the Prophetess Hannah, 1631. Wikimedia Commons

Thus, if we return to a New Covenant understanding of church life, then we see that there is nothing which in principle is impossible for a woman or inaccessible to her, which would keep her from bringing forth prayers of thanksgiving and the anaphora on behalf of the church gathering. After all, if we look at each of the parts of this prayer: preface/introduction, remembrance/anamnesis, epiclesis/calling forth the Holy Spirit, intercession/petition, then we see nothing which should prevent a woman from being able to bring these prayers before God on behalf of the church community. What could be the problem? Does she not have a memory? Is she unable to proclaim the initial words of thanksgiving? Is she not able to call forth the Holy Spirit? Any believer can do these things. Can she not make petitionary prayers on behalf of others? She can. True, under the Old Covenant, a woman couldn’t do these things. But under the New Covenant she can. Thus, if we look at each of the component parts in an organized way, we see that a woman can do all these things. So why is she forbidden from bringing all of these parts together as a whole?

What does she really need in order to be able to celebrate the Eucharist? The gift of prophecy, which remains unrealized and forgotten in an ecclesiological context to this day. Just as it has been forgotten and not fully recognized that it is not a stand-in primate that is needed for the charismatic celebration of the Eucharist, in general. What is needed in the congregation is a chairman – as was said in ancient times – but not a stand-in primate.

So what is the difference between a chairman and a stand-in primate? A chairman is someone who is the elder at common table or in any sort of responsible gathering. If we are talking about society, for instance, we might speak of the chairman of the parliament. In fact, it would sound crude to us to speak of the “stand-in primate of a parliamentary gathering”. But when, for instance, the tsar showed up somewhere under a system of absolute monarchy, he behaved exactly as a stand-in primate. Even if he just sat there in the chair, everyone received him as the hierarch in relation to everyone else. He is “over” everyone else. Both the Pope and the Emperor are “above” everyone else – and this is where papism and papal-imperialism and imperial-papism all come from. So, when we talk about the ministry of church elders, we need to distinguish between leadership by stand-in primates and actual chairmanship. A stand-in primate is always needed in a hierarchical gathering, but in a church community or brotherhood, a chairman is needed.

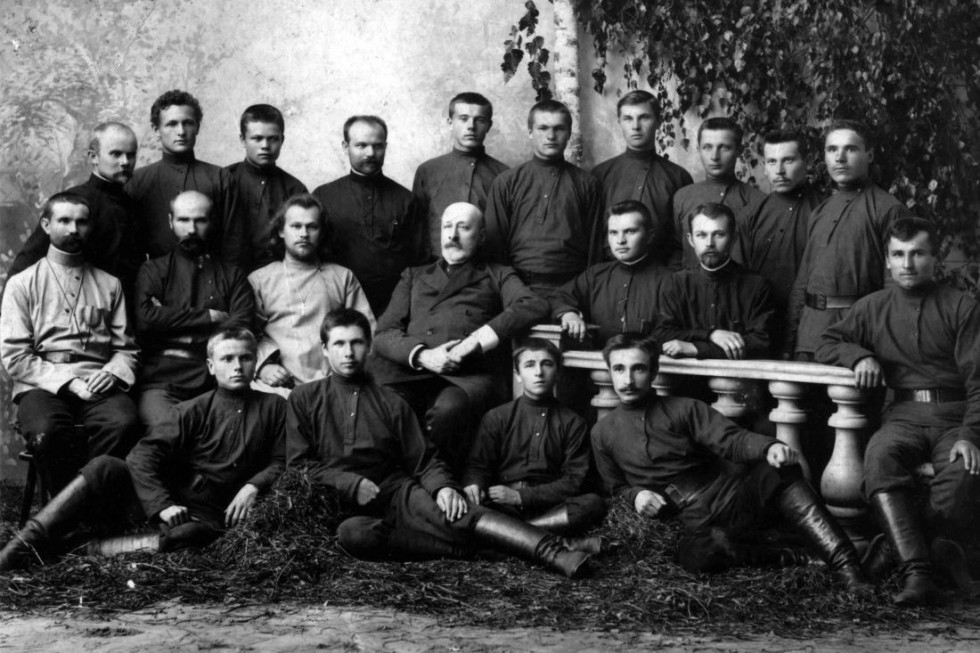

Members of the Orthodox Workers Brotherhood of the Elevation of the Holy Cross, 1904-1907.

In the church we could go further, so as not to once again get caught up in the temptation to hierarchism or, in other words, return to the Old Covenant. We could, at our Eucharistic gathering, remember not so much the Mystical Supper, as the washing of feet and the coming of the Holy Spirit at Pentecost.

The washing of feet is often, and in an unjustified manner, placed in parallel with the Last and Mystical Supper. But in the context of the Gospel, these events are not connected in any way, and it is as if they are generally invisible to each other. It is no mistake that the Gospel of John has an account of the washing of feet but does not record the Last Supper, while the other Evangelists have an account of the Last Supper but don’t tell of the washing of feet. The washing of feet is the image of Christ’s kenosis, just as is the Last Supper. They are both prototypes and antecedents of Golgotha. But in the washing of feet we also have a sort of passage from symbol to that symbol’s realization and enactment. This is, of course, not yet Pentecost, but it is considerably closer to Pentecost than is the Mystical Supper. The Mystical Supper comes prior to Golgotha, but Pentecost actualizes the New Covenant – the birth of the Church of Christ as the Church of the Holy Spirit. Before that, the Church of Christ was only a collection of disciples which were, as of yet, incapable of teaching anything themselves, but could only study and learn.

The Mystical Supper will always come before Golgotha: it points to Golgotha and is its prototype. It leads to Golgotha. The Church needs it, because its remembrance of the Mystical Supper is always important to keep, but sometimes, perhaps, not as the main thing, let alone the only content of the Mystery of the Eucharist. We need the Mystical Supper because the New Covenant is enacted at Golgotha. If man is only still on his way to that moment when the New Covenant will be enacted in his life, or if he is only just beginning that life in the New Covenant, then the Mystical Supper will occupy the place of honour. But if he wants to bring forth the fruits of life within the New Covenant then he needs Pentecost, which at this point comes forward to occupy that place of honour. And the washing of feet is closer to Pentecost than the Mystical Supper. In the washing of feet, the Mystery of Christ’s love is revealed to us not only as pre-enactment, but as embodied action. This event already opens up the content of life in the New Covenant, rather than only speaking of its possibilities. The Mystery of the Last Supper is, without question, tied directly to Golgotha: “this is my body”, “this is my blood” – and this is the main thing at the Mystical Supper. Although it is also important that the participants commune at common table, and that this fellowship and the community itself are found here.

Thus, while it is still possible to view the Mystical Supper as a hierarchical common table in the Old Covenant sense, leading to Golgotha, then Pentecost is something entirely different. Although Golgotha itself is the revelation of a new reality, as is Pentecost. But these revelations are nonetheless different from each other, as if they are different levels of revelation, although both can have their expression in the Eucharist. I am sure that if on the day of Pentecost the apostles celebrated the Eucharist – and of course after the Coming of the Holy Spirit they came to the Eucharistic table with all who had believed – then it wasn’t just a remembrance of the Mystical Supper and of Christ who had just given them the Holy Spirit and New Life and opened the doors of the Kingdom of Heaven to them. And this is a type of non-hierarchical Eucharist, oriented toward the event of Pentecost.

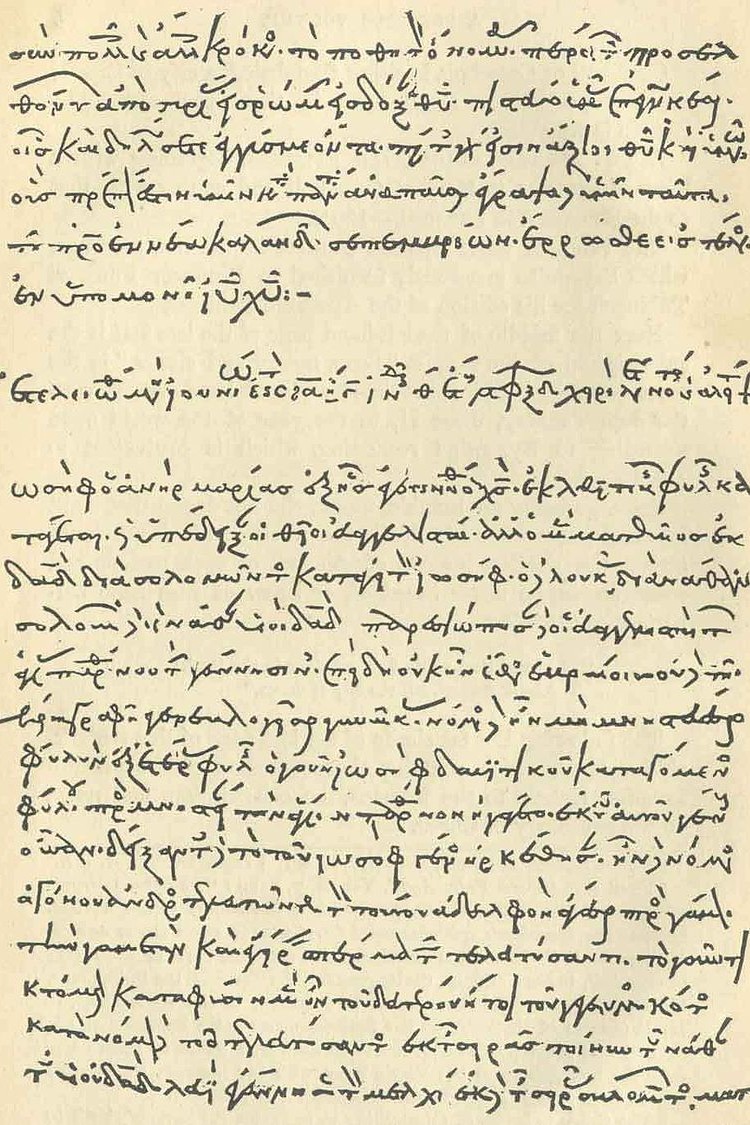

The Didache is the only full text which speaks to us directly about this. In all the other sources which have been preserved, we find only tangential and fragmentary references. But in the Didache, the accent is on the New Testament reality, on the new revelation and vision, the new faith and eternal Life, opened through the Child Jesus, and also on the Church gathering from all corners of the earth as the united Body of Christ, as an image of the one bread, broken, and on its refinement in the Love of Christ. We also read here a resolution to the effect that prophets be provided the opportunity to celebrate the Eucharist without time limitations, however much they desire to celebrate.

Fr. Nikolay Afanasiev believed the Didache to be either a forged document or an example of unorthodox teaching in an unorthodox book, because it describes something entirely different from the Eucharist which he writes about and which appears in other sources that have come down to us in, for instance, the writings of the Apostle Paul, in which the Apostle speaks primarily of the Mystical Supper saying: “For I received from the Lord what I also passed on to you: … For whenever you eat this bread and drink this cup, you proclaim the Lord’s death until he comes.” (1 Cor 11:23–26).

Colophon with the date of the Didache manuscript, 1056.

I think that the Mystical Supper began to be remembered in Christian communities as early as in the 1st century, when this celebration didn’t yet disturb the charismatic mood or the community and brotherhood structure of the gathered church. It was, however, unavoidable that from this would grow a hierarchical church structure; after all, at the Mystical Supper itself, even as He was moving toward His own voluntary death for the life of the world, Christ was a hierarch to his Disciples, who still didn’t possess the gift of the Holy Spirit. And when the Eucharist came to be celebrated exclusively as an image of the Mystical Supper, natural logic led the church into a situation in which the primate himself began to be received as a hierarch, i.e. as a single, unified head of the community and the church, as someone of a different order from the gathered people of the church. And this gradually allowed the headship of Christ to disappear from view. The seriousness of this change – not only in terms of its meaning for the sacrament and ecclesiology, but most importantly in an existential and mystical sense, is to this day not fully appreciated.

Unfortunately, we have very few sources which speak about how the Eucharist was originally celebrated in the early church. But it is completely clear that the entire divine economy of the Church was called to remembrance, including the Mystical Supper, and the Gift of the Holy Spirit at Pentecost, and that one or the other might be accentuated. The epiclesis, at least, speaks to the fact that Pentecost is always remembered at the Eucharist in one way or another.

The idea itself of a Christian meal of thanksgiving was an extremely good one, but people somehow often forget that originally and until the mid-2nd century, this common table wasn’t only Eucharistic, but was in the first place an Agape meal, which was only completed in the celebration of the Eucharist. And an Agape meal is usually non-hierarchical, in contrast to the Eucharist as celebrated in our contemporary understanding. And the fact that the Eucharist was then only the culmination of the Agape meal of the community or brotherhood is testimony to the fact that it was originally non-hierarchical. At a later date, the Agape meal and the Eucharist switched places, and the Agape became the culmination of the mystery of thanksgiving, rather than its beginning. Externally, this happened only for reasons of honourable intention, in order to preserve adequate reverence and respect toward the body and blood of Christ. But in essence, this was a major revolution in the church, specifically because in this way the door was flung open to the emergence of hierarchy in the church, as well as to the introduction of law and right and, as a result, of legalism and the formalization of the faith, so that Christianity could be transformed from a method grounded in a new type of life into a religion, which is always partial and always edged out into the private sphere. And it was this, in particular, that lead to nationalized Christianity. This main glitch or mishap, from which then grows the entire Constantinian Era of Church History, happened in the mid-2nd century, although the makings of these events can be found already in the 1st c. – almost from the very beginning, from the time of the Apostles (if we keep in mind all four initial apostolic types of church tradition – not only Johannine, but Pauline, Petrine and Jacobite).

Of course, we need to remember that circumstances which prevent the discovery of spiritual gifts are always present in life. To live charismatically was always difficult, but, nevertheless, the church somehow recognized and admitted her prophets and itinerant apostles (i.e. direct disciples of the apostles who didn’t live in community, and travelled between communities, in order to actualize the catholic ties between communities, because otherwise, without real links, these communities would have come to nothing, as Archbishop Kirill Gundyaev once told us when I was in seminary and he was still rector.) And these days, even if there are perhaps still itinerant apostles and prophets somewhere, then they are in the form of holy fools. This means that our church society – those who belong to the reigning order and morality – don’t accept these apostles and prophets as their own. But the church never takes just one form. She always has a multiplicity of forms, and there are always real saints, including authentic charismatics, within the church.

All of this applies not only to the Orthodox Church, but to the Catholics, and to the Protestants. Unfortunately, this topic is entirely unrecognized and undeveloped. People must still come together within the church, and they will speak about all this.

First published: Media Project «Stol»