The Royal, Priestly and Prophetic Callings of Women in the Church

Christ is Risen!

Happy Feast, Brothers and Sisters!

Well, yet another week has gone by since Pascha. How time flies. Having completed our contemplation of the revelation of Christ’s Holy Resurrection, which we have received by the grace of discernment and, even partly, by the doubt of the Apostle Thomas, we have moved on to our celebration of the memory of the Myrrh-bearing Women and several other saints, among whom are the sisters of Lazarus, Mary and Martha, and St. Tamara, Queen of Georgia.

In the course of our church year, we are not given many opportunities to contemplate our wonderful Christian sisters in the Church, or women and woman’s ministry in the church, in general. Perhaps it makes sense, therefore, for us to redress that deficit to some degree at this moment.

In fact, we have happened upon a very particular issue here. Although everyone knows that there are a great number of women in the church – at any rate in the Orthodox Church – somehow they are forgotten. They are just there in church life like some kind of permanent background. On the other hand, whenever there are too few brothers, the brothers start taking on the tastes and opinions of sisters, and even sometimes start resembling them a bit.

Moreover, from scripture we learn that in Christ “there is no male nor female” (Gal 3:28), because in the Church everything that has to do with purely human differentiation somehow goes away. These differences become less than important, not very significant and are not part of the framework of our life in Christ. On the other hand, the Apostle Paul himself says that women should keep silent in church (1 Cor 14:34). If they are really curious and sharp, let them ask their husbands about what they have heard in the church gathering (1 Cor 14:35), and let their husbands teach them. Because “the husband is the head of the wife” (1 Cor 11:3), and that pretty much says everything. He, as the elder, should teach those less senior. This is normal church tradition which comes right out of Old Testament times and, probably therefore in some lawful way remains valid for the time of the New Covenant. So what should we do with all this?

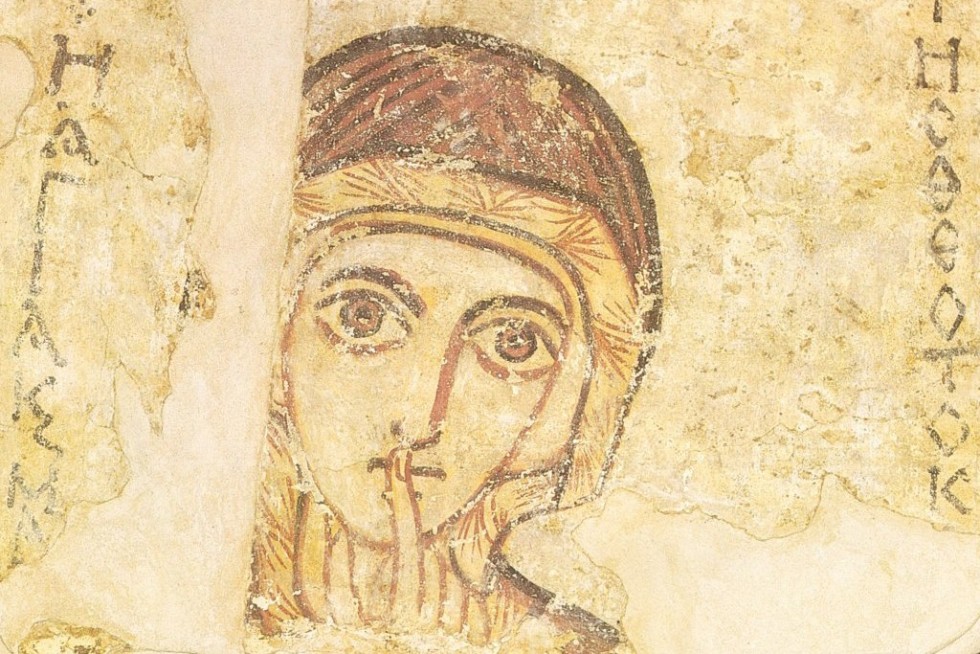

St. Anna. A fresco from Faras, Sudan (Nubia). National Museum, Warsaw. 8th c.

Everybody knows at this point that women’s place in the church is currently played down. And it’s a fact, that although there are very many women in the church, they often have little education, and if they are educated, they generally work somewhere else, in a sphere that has little to do with church ministry or solving the difficult spiritual problems which are related to teaching and mentoring and all else which is generally seen as belonging to Christ within the church and to those who, as it is something thought, sit in Christ’s place within the church gathering.

Of course, here we should immediate mention that in the ancient church nobody “sat in” for Christ in the church gathering. But, then something serious changed within the church, and already by the mid-2nd century, a new era in Church history began – an era related to so-called Eucharistic Ecclesiology. It is here, precisely, that masculine hierarchy is born, and some saints begin to call upon the people of God to look upon the arch-pastor as upon a high priest, specially separated out from among a nation of priests and kings, almost as if he is God himself. For instance, we see this in St. Ignatius of Antioch in the second half of the 2nd century. And this is serious.

Before this time, however, women had occupied a worthy place in the church. They could even prophecy – a male or female prophet, in his or her standing, was in essence in a place of honour higher even than bishops – directly after apostles. And here there wasn’t a difference between women and men prophets. True, this era came to a close fairly quickly, and is almost completely gone by the middle of the 2nd century and, in the centuries to follow, the ministry of prophecy barely achieved a minimal existence, which is fully understandable.

So let us look at what church life was like in the beginning. As early as the 1st century, we can see vestiges an Old Covenant attitude toward women, as if they are second-class citizens of the people of God, the Christian people, and that entirely new vision – by which purely human differentiation begins to take a backseat – loses its primary significance.

What, at that point, could women in the church do that men could not, and vice-versa? What could men do that women could not do? This question has tortured the Christian conscience since time immemorial. There are a lot of answers to this question, including some well-developed answers – and they always include the thought that we really don’t fully know. That’s fair, but nevertheless… So men were apostles? Yes, but there are women who if they were not apostles proper are called “equal to the apostles”. We remember St. Nina of Georgia, St. Helena and St. Olga as equal-to-the-apostles, or Mary Magdalene of the Myrrh-bearing women. This means that women could preach and were participants in the mystery of the proclaimed word in an equal way with men. And I’ve already spoken about prophecy: prophets could be either sisters or brothers.

Queen Tamara of Georgia, called “equal-to-the-apostles”. Fresco. From the cave-monastery at Vardzia, Georgia. 12-13th c.

So what does the continuation of the history of Christianity show? When the era in which the mystery of the Eucharist was to be celebrated only by a single hierarch arose – the only bishop or senior elder, at this point it turned out that women could also perform liturgical mysteries, up to and including baptism and – scary to say – serving communion. They could be at the head of entire church communities and, it seems, pre-Eucharistic or (from the second half of the 2nd century) post-Eucharistic agape meals, which were also themselves sometimes referred to as sacramental mysteries. At that point, these women were called “presbyterides”.

These presbyterides are yet another mystery of our church history and tradition. Yes, it seems that they could preside – especially in congregations of women – they could lead prayers in the congregation. And this didn’t bother anyone. They could probably also baptize. And it was only in the 4th century, for reasons that aren’t entirely clear, that in one of the provinces of the Roman Empire the ministry of presbyterides was recalled, and somehow this was accepted by everybody, which is understandable in the Constantinian Era of church history, in the context of territorial-parish and diocesan ecclesiology.

We know that from the 1st to the 10th century there were deaconesses in the Church, and we see them mentioned already in New Testament scripture. This means that women could perform the ministry of compassionate and merciful works, “the mystery of brotherhood” was opened to both brothers and sisters. And, in later church history, it is no coincidence that the laying on of hands in the case of dedicating deaconesses was performed in the altar. Their vestments include both surplice (stikharion) and stole (orarion). On the day of the laying on of hands, they received communion at the altar, right after the deacons. They could also help with baptisms, especially the baptism of sisters, and in cases of real need could themselves baptize them.

Grand Duchess Elizabeth Fyodorovna raised the question of restoring the order of deaconesses for the discussion of the Holy Synod when she founded the Martha and Mary Convent, in 1909. Afterwards she petitioned the state for the restoration of that order

So we see that sisters could do practically everything, and were not in the least diminished in comparison to brothers within the church. The only real question is whether then could celebrate the Eucharist itself – i.e. the mystery of thanksgiving. The mystery of distributing communion they could, but the mystery of giving thanks? This is a very fraught question. Although we do know that women could be prophets, and that prophets could preside at the Eucharistic gathering. In ancient church books it is said “permit the prophets to make Thanksgiving as much as they desire” (Didache 10:7). True it does not say “woman prophets”, though no fundamental difference is mentioned anywhere. It is true that we don’t have a single direct witness to the event of a woman prophet celebrating the Eucharist or preside at Eucharistic gatherings of the church. But we have very few sources on church life in general before the mid-2nd century. But a fact remains a fact: we don’t have a single witness to a woman presiding at the Eucharist. True, neither do we have witnesses saying that this is forbidden.

Should we consider this happenstance? Perhaps this is omission – cultural and spiritual inertia? Not so much tradition as inertia? Under the Old Covenant, it would have been difficult or even impossible to consider women serving in these ministries, and under the New Covenant until about the mid-2nd century, in fact, the Jewish influence was very strong. And when the Hellenic influence increased with an influx into the church of pagans – who had a tradition of both priestesses and prophetesses – the picture within the church changed. But with the inception of church hierarchy in the mid 2nd century it became more difficult to conceive of women celebrating the Eucharist. At the time of Tertullian at the end of the 2nd and beginning of the 3rd century, the Montanists tried to restore formerly active women’s ministries, and it is no co-incidence that the founders of this movement were, specifically, Phrygian prophetesses, though at this point there was already resistance from the catholic church, as is logical given that the conditions of Eucharistic ecclesiology had by then prevailed.

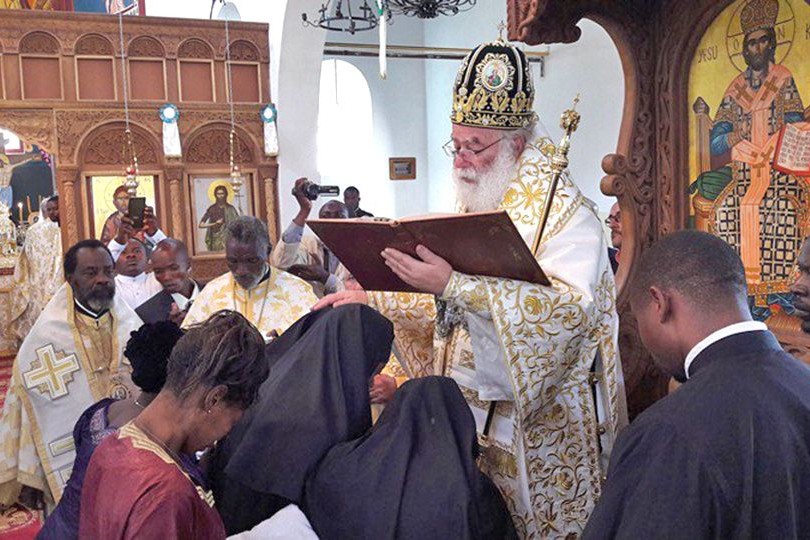

So we have a very interesting picture which tells us that church tradition, although it developed at times in different ways, contains within itself enormous potential in terms of the ministries of women – potential which can presumably be revived. The order of the deaconess and their ordination by laying on of hands has already been reborn within a number of Orthodox churches, as you know. This is primarily true in the Patriarchate of Alexandria. This is spoken of more and more in various circles within other Orthodox churches.

Consecration of women to the order of deaconesses. Head of the Church of Alexandria, Patriarch Theodore II

We need to revive women’s holy ministries to the extent to which the church has need of these. This is an enormous potential force and energy of reason and spirit, which the church should use better than she has for many, many centuries. It is clear to everyone at this point that women can do more than be priests wives, do the dirty work of cleaning floors and lampstands in the church, or, at best, be altar servers if they are monastics or “widows”.

In a word, in the ancient church there was a ministry of “widows”, which was one of the particular ranks for women, usually old or single. Their service, more than likely, was similar to diaconal service, though it isn’t at this point very clear how the ministries of “widows” and “deaconesses” differed from each other. We might assume various things, but we don’t really know. It is clear only that in the ancient church these were two different services which were not mixed. Perhaps “widows” served women without families, old men, and brought up children.

On the road to restoring women’s ministries within the church, at this point we can see both difficulties and achievements. During the 20th century, the issue of women’s priesthood arose, but was incorrectly understood, interpreted, and put into practice. This, despite the fact that the idea itself was, perhaps, not bad. There was a desire to take advantage of the great potential of our sisters in active church life. But, churches went at it in a little bit of a mechanistic way, unfortunately, just using the same form by which brothers serve as priests. They even started ordaining these women in the same way that bishops and priests are ordained, etc. The tradition of the ancient church wasn’t entirely taken into consideration, and this drew criticism from the catholic churches, both Orthodox and Roman Catholic, which did not recognize this practice as traditional or justifiable. And, although serious theological arguments against women’s priesthood were not made – and perhaps they don’t even exist – tradition is a stubborn thing. So the catholic churches made reference to tradition, and this had its own kind of truth and strength.

Nikolay Ge. Messengers of the Resurrection. 1867

Today we celebrate the memory of the Myrrh-bearing women who were the first witnesses of the Resurrection of Christ. We celebrate the memory of Martha and Mary and the memory of Tamara, Queen of Georgia. We remember that here in Russia several queens have also been canonized, although this ministry of being at the head of a kingdom is also something the history of the church cedes to women only grudgingly. Nevertheless, we remember these cases, including those in Russian history. Though these tsaritsas and empresses were often far from canonical standards in their personal lives, though they could be the protectresses of the church and rule on many questions of church life.

So we’ve touched on all the most fundamental aspects of church ministry, including that of the king, the priest and the prophet. Sisters can be queens or prophets, but priests, it would seem, they can be only partially. It is not clear what will happen going forward, but for the moment it is impossible to imagine women bishops or priests on the model upon which we have bishops and priests (all men) today. But may I remind you here that our contemporary image of priestly or episcopal ministry is far from that of the early church, which is true also for deacons and deaconesses, by the way. We’ve endured tremendous changes, about which Nikolay Afanasiev, Sergei Bulgakov and others have already written.

So nearly all charisms are open to our sisters. If we wanted to picture a some sort of sister-prophet – a thing which is entirely possible – who would come into the church as someone with authority…what exactly might we see and what could we possibly say against such a thing? We would probably see that she could preach in the church gathering, just as any who have the gift of words and witness – just as bishops, priests, and sometimes deacons and laymen (male). And sisters can do this, too. We already know of cases like this. Could a woman prophetess lead a church gathering? I fear she absolutely could. In particular and difficult conditions – easy for us to imagine at present – she probably could. She could train, baptize, and be the head of an Orthodox community or even a whole church brotherhood.

Mother Maria (Skobtsova) – an original thinker, theologian, preacher and founder of the Orthodox Affair (Pravoslavnoye Delo) charitable and cultural-educational society. She died a martyr’s death in the gas chamber at Ravensbruk on 31 March, 1945

We have only to admit that practically all the ministries which our brothers perform could also be performed by sisters, if they have particular spiritual abilities and gifts. Only if we are speaking about the Eucharist – about thanking God for Christ’s sacrifice and for our inheritance of the Kingdom of God – if we are talking about the prayer over the Eucharistic sacrifice and over the gifts of bread and wine at the Eucharist (rather than at an agape meal) – here, probably there would be difficulties.

But, we might imagine a different version of events, where we reject anew an understanding of the Eucharist as a sacrifice and, it follows, as about priesthood as hierarchical priesthood and restore the New Testament understanding of the priesthood of all believers, for which the only High Priest in the Church is Christ himself. Then sisters, too, as members of the People of God, might praise and worship God, “showing forth the praises of Him who has called us out of darkness into his marvelous light.” (1 Pet 2:9). In doing so, can they thank God? They can. Can they lead agape meals? They can. As such, if we do not place so much of our church attention on hierarchical priesthood and on the Eucharist as sacrifice, then a question appears: what exactly would prevent sisters from pronouncing the Eucharistic prayer of the Church and thanking God for Christ in approximately that form in which this is expressed in the Eucharistic or agapic prayers of the Didache?

One of the greatest Orthodox theologians of the 20th century, Fr. Vitalij Borovoj (also Professor), told me at one point that in the Orthodox Church there are really no theological arguments against women’s priesthood, understood in terms of presiding at the Eucharistic gathering – there is only tradition and habit. In our time, when the church has long ago outgrown the inertia of the Jewish consciousness which found it impossible to imagine women priests in the temple, and when understandings of hierarchy in connection with Eucharistic ecclesiology and the teaching about the Eucharist as a sacrifice are slipping away, we might – with great caution – presume that the question of the fullness of women’s ministry in the church is becoming relevant like never before. And really, in a case of need, for instance, if there is no possibility of finding a bishop or a senior pastor to ordain a new leader of a Eucharistic gathering, or if there isn’t a worthy candidate among the men to appoint as elder in a Christian community, then just perhaps, under the influence of our coronavirus circumstances I am tempted to say – a mutation might occur. And, that which hasn’t previously happened in history might suddenly come about. Only we can’t do this in an arbitrary way or just because we want to experiment, or simple on the basis of historical and logical conclusions, even if they are theological. Mutations can be foolish, cause harm, be pathological, cause disease and even death, as with the coronavirus. But they can also be positive and useful for the church and for the people of God.

I do not want to prompt any conclusions or point anyone, God forbid, in a particular direction. I simply want to say that our tradition is flexible and living, and that the authentic potential of our Christian sisters – be it spiritual, psychological, material, or physical – is extremely great and in no way fully in use. This potential holds its own mysteries and unrevealed opportunity.

If we come at the issue this way, then the memory of the myrrh bearing women, the women equal to the apostles, our Holy Orthodox queens, prophetesses and holy deaconesses and widows – and perhaps women priests – becomes particularly significant and precious for us. It is by no mistake that there is an ancient story in the church, which tells how the apostle Paul was accompanied by holy women. One very important 2nd century apocrypha, The Acts of Paul and Thekla, speaks of this. Holy Thekla, equal-to-the-apostles, may also have been a prophetess.

St. Thekla. Fresco. Cathedral of the Holy Transfiguration, Chernigov. 11th c.

Brothers and sisters – let us be very attentive to the inheritance that we have. Let us think also about how if we men, the brothers in the church, continue to perform our ministry in the church poorly… who knows? Others might just be found to take our places, and a healthy mutation might take place in church tradition. And, although this is probably a joke, we may just find that there is a kernel of truth in it.

Amen.

Christ is Risen!