Between Eucharistic Ecclesiology and the Reality of Parish Life

Professor Petros Vassiliadis and Fr Georgy Kochetkov

The point of departure for discussion was the eucharistic ecclesiology discerned in the 20th c. by an outstanding Orthodox theologian, Fr Nikolay Afanasiev. Eucharistic ecclesiology is a reconstruction of the rules of church life and an attempt to break through years of sediment and distortion to the original spiritual experience of the ancient church, as brought to us through early Christian texts.

Father Nikolay’s prophetic intuition, which is widely recognized in Roman Catholic as well as Christian Orthodox circles, was an extremely powerful stimulus toward the renewal of church life. This is true not only because he provided an alternative to the leading ecclesiology of the time, which accented the external hierarchical structures of the church, but also because Fr Nikolay’s intuition gave food to theologians and active church members who, like Fr Nikolay, wished to see the church first and foremost as the gathering of the people of God, and had before them a series of difficult questions.

Key among them was the question of the Eucharistic gathering itself. How does it come about? Where are its boundaries? Whom should we consider a member of such a gathering? After all, in his reconstruction, Fr Nikolay doesn’t just describe any old sort of church – he doesn’t describe a church of catechumens or seekers, but what Sergei Fudel called “the church of the faithful”, which is an ingathering of people who give their hearts to God and do God’s work in the world.

David Gzgzyan

As an established part of the spiritual experience of church renewal lived out by active representatives of the Russian emigration, Fr Nikolay’s theological intuition bears witness that the Church he discerns in his works is more than simply an ideal. The search for the authentic evangelical life which comes from Christ and has universal, constitutive significance for the church, gives Fr Nikolay’s theology a prophetic power and persuasiveness; it isn’t a coincidence that the Eucharistic gathering in his work looks more like the subject of a sermon than it looks like a theological construct.

Dmitry Gasak, Vice Rector of SFI, presented a paper entitled “Types of Ecclesiology in the work of Fr Nikolay Afanasiev and other attempts to classify ecclesiologies within the Orthodox Church”

But, like it or not, the boundaries of this wished-for church turn out to be beyond our current church reality and remain – in the words of one conference participant – in the field of God’s hope.

Fr Nikolay wanted to see the people of God in the church – the common people, but not a “worldly” people, calling into question even the use of the Russian term “miryanin”, to mean “layperson”. (The Russian word “miryanin”, which means “layperson”, has the word “mir”, which means “world”, as its root.) As St Philaret’s Rector Fr Georgy Kochetkov reminded conference participants, “to call a participant of the Eucharistic gathering a ‘miryanin’ is simply impossible: the Greek word ‘laïkos’ can’t be translated as ‘miryanin’. Rather, it means a member of the people of God and, when we speak of the royal priesthood, we do not have anything at all that is ‘of this world’ in mind.”

Is it possible to find or to create such a gathering in the context of contemporary parish practice? What constitutes a church gathering and how are its boundaries determined? How do we imagine the search for God and what do we mean when we speak of a Christian’s participation in the life of the church? What exactly is that life?

To a great extent, contemporary parish life is focused around rites and mysteries which are left to one’s individual understanding and seen as a path to health and well-being, more often than not oriented toward servicing the earth-bound demands of people’s biological and cosmic needs. This worldly and rite-based paradigm for church life leads to a situation where the demands on church members and requirements for the church’s boundaries are determined by rite-based criteria and therefore entirely consumerist, conforming entirely to the needs of this world. In practice, a person is considered a Christian if, from a ritual point of view, he has been baptized in a more or less normal fashion and with some sort of regularity goes to confession and communion (while the quality and regularity of confession, as well as its connection with real life, remain a separate and looming question).

With this sort of emphasis, the energies of this world erode away meaningful content and, if one so wishes, he can live as if by himself and by these energies, remaining untouched by and deprived of communion in the church. The spiritually seeking person, on the other hand, has demands which are “not of this world”. He cannot come to the truth without Christ or the assembly of his disciples and is, in the words of Sergei Fudel, “forced to look for the Church within the church.” It would be more accurate to say that the average parish is in need of intelligible witness to Christ than that it is able to provide this witness to a person from the outside.

People want to find the flowing stream of Christ’s abundant life – filled with the spirit and meaning of the gospel – so as to be nourished by Christ’s life and enter into its depths. But usually in a parish they find only walls between the altar and the nave, or between the church-corporation which doles out ritual services, and the laypeople with their physical needs, who consume these services.

In the 20th century, the question of the church’s boundaries was one of the primary ecclesiological questions. Frs Sergei Bulgakov and Georgy Florovsky, when considering the “contours of the body”, differentiated between her mystical boundaries, the limits of which extend to include all of creation, and the empirical or canonical boundaries of the local community. Similar distinctions (Church with a big “C” or church with a small “c”) have remained in wide use. Fr Nikolay Afanasiev, retaining this distinction, moved the emphasis from the canonical to the mystical Church, which stimulated inter-confessional dialogue, insofar as he recognized the legitimacy of the mysteries outside of the canonical boundaries of Orthodoxy.

Olga Kuznetsova, a graduate of SFI, explains how theologians in the 20th century reckoned with the question of church boundaries

But if the Mystical Church of Christ is made manifest in the Eucharist, does this also imply that she – “Una Sancta”, “the people of God”, “the Church of the faithful” – is created in the celebration of the Mystery of the Eucharist?

Fr Alexander Lavrin

Fr Alexander Lavrin reminded us of a discussion that evolved several years ago around the question of the frequency of Holy Communion, as a result of which many of us agreed that coming to liturgy made sense particularly because of our communal reception of the Holy Mysteries. But in considering the question of how this affected the community, Fr Alexander noted that “although an understanding of new concepts can cause a person to search thoughtfully and work things out, it in itself is not able to change his interactions with God and man, which lie at the foundation of the spiritual life.” “If there isn’t movement in that direction, then frequent communion will bear no fruit,” said Fr Alexander. A person will nevertheless continue to live ‘alone’ in a life that is absolutely worldly, in the external sense.”

Fr Georgy Kochetkov

This contradiction is resolved in a closer look at the question about the church’s boundaries, thinks Fr Georgy Kochetkov, Rector of SFI. He believes that in addition to the mystical and canonical boundaries of the church, we must also look at the sacramental boundaries. The mysteries, in and of themselves, don’t bring about the Eucharistic community. The mystical boundaries of the Church are known only to God: “we know where the Church is, but we don’t know where she isn’t.”

Fr Georgy reminded us that the ancient church depended heavily upon the prophetic service – a service of the word – and that probably it was this, more than anything, that formed an assembly that was able to bring thanks “with one heart and one voice”. Contemporary church life, in which the prophetic is unrecognized and often belittled in false modesty, provides little basis for hope for renewal “of the central services, which were typical of the early church”. However Fr Georgy is sure that “there, where the Spirit is free, you can find the Church, and saints, and communion in the gifts of the Spirit”: services in the church which are related to the revelation of the spirit and meaning of the Christian life – services such as teaching the life of faith, preaching the gospel in the church, shedding light on the mysteries of the faith – these services undoubtedly partake in and of the gift of prophecy.

Petros Vassiliadis

Professor Petros Vassiliadis of Aristotle University in Thessaloniki commented on Fr Georgy’s thought that it is necessary indeed to distinguish between the mystical and sacramental boundaries of the church, saying that a fundamental misunderstanding of the Greek concept of “mysterion” is prevalent. In early Christian texts this term is not used to mean a sacrament, but rather to speak of God’s design to save and transform the world, the boundaries of which at their limits should coincide with the boundaries of the Church. He reminded us that the ancient church in fact distanced itself from an understanding of the Eucharist as a “sacramental cult” and, in this sense, the failure to distinguish between the mystical and sacramental boundaries of the church really does lead to considerable confusion.

Professor Vassiliadis believes that baptismal ecclesiology (a theological development introduced by Fr John Erickson) more accurately articulates the qualitative boundaries of the church, focusing on the problem of our first and only consecration as members of the people of God, which happens – or, at least, should happen – at Baptism.

Fr John Behr, of The Dean of St Vladimir’s Seminary in New York, participated in the conference in absentia. Fr John associates Afanasiev’s accent on the Eucharist with the particular spiritual experience had by Afanasiev, Schmemann and others from the Russian Emigration. In this sense, Eucharistic Theology isn’t so much a reflection of the 2nd century, as Fr Nikolay tried to reconstruct, as much as it is a particular reading of the 2nd century by specific theologians who live in the 20th century. Having said that, Fr John expressed the thought that the reduction of the question about boundaries of the Church to the performance of sacraments inevitably returns us to the principle of the territorial parish and to episcopal ecclesiology.

Marina Naumova, a vice-rector at SFI, presented a paper entitled “The service of lay people in the ecclesiology of Fr Nikolay Afanasiev and Contemporary Church Documents”

Zoya Dashevskaya, Dean of the Theology Faculty of SFI

In the opinion of many contemporary theologians, one of the most topical questions in ecclesiology these days is that of the role of lay people. And the most telling gap between theological theory and life, says Professor Vassiliadis, concerns the service of women. As far as we can tell from New Testament texts, the ancient church didn’t have a problem with this at all; the service of women was a fact of life that didn’t require justification. Discussions on the matter began only in the 2nd century when the church began to grow into a traditional structure within Roman society. Gleb Iastrebov, senior lecturer at SFI, presented a reconstruction of the imagined service of sisters within the ancient church based on New Testament texts.

Of course, ecclesiology is a local phenomenon – an attempt by such an insignificant minority within society as the church to “measure its own pulse”, make sense of its trajectory, goals and calling within the world. But, in fact, this symposium spoke of questions related to the quality of that tiny quantity of salt, which is called to conserve the world from rot and convince man to resemble itself, which means to resemble our Savior, too, if only in a distant fashion. And in order to answer that call, it is very important for the church to remind herself from time to time that she isn’t sustained by the “properness” of her mysteries or by a particular sacral structure, but by the fact that she is the place where we have access to seamless connection with God and neighbor – our only chance to come to ourselves and become partakers of eternity.

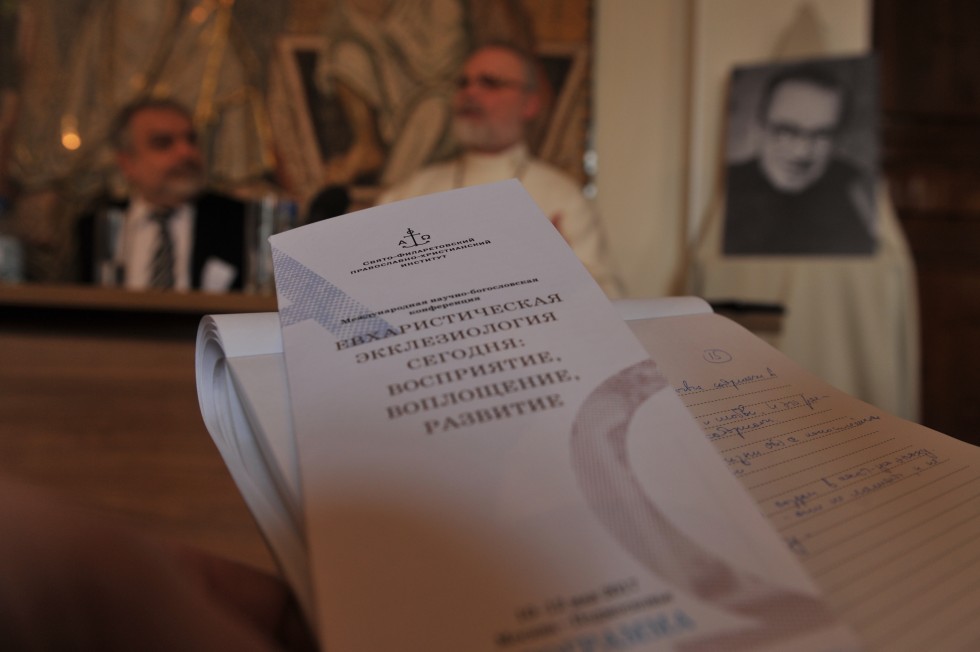

97 people from 25 cities and 18 Diocese within Russia, as well as from Greece and America took part in SFI’s Symposium, entitled “Eucharistic Ecclesiology Today: How we Perceive, Apply and Develop it”. Dozens of representatives from both secular and religious institutions of higher learning were present. The Symposium consisted of 2 round table discussions and the presentation of 14 academic papers.

David Gzgzyan

Fr Georgy Kochetkov

Oleg Glagolev

Alexander Kopirovsky

Larisa Musina

Fr Sergey Rybakov

Gleb Iastrebov

Grigory Goutner, Tatiana Pantchenko

Svetlana Chukavina

Evening Programme: “Images of the Church of Christ in Russian Culture”