The Boundaries of the Church, the Role of Laypeople and Church-State Relations: Key Questions in Contemporary Ecclesiology

The 6th century Byzantine mosaic in the apse of the basilica of Sant’Apollinare in Classe (Ravenna, Italy)

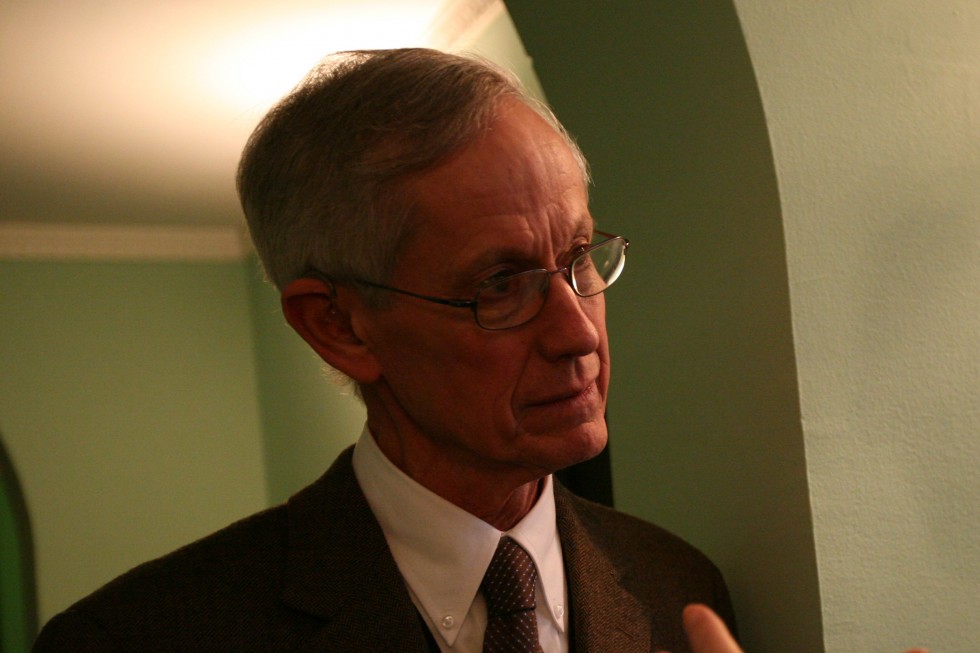

Metropolitan Kallistos Ware

Metropolitan Kallistos Ware: In the area of ecclesiology I consider that the two most important issues are: (a) How to strengthen the relations between the different Orthodox Churches, and to promote a clearer visible witness to pan-Orthodox unity (building upon what has been done at the Conference in Crete last summer); (b) How to provide a satisfactory canonical solution to the situation of the so-called ‘Orthodox diaspora’ (that is to say, the Orthodox communities in the western world outside the limits of the traditional Orthodox countries). This will involve a careful assessment of the prerogatives and responsibilities of the Ecumenical Patriarchate in the worldwide Orthodox Church.

Petros Vassiliadis

Petros Vassiliadis: The most relevant area is the contextualization of the Eucharistic ecclesiology, first advanced by N. Afanasiev, but aiming at questioning the excesses of the universal ecclesiology. With the almost complete disintegration of the Orthodox Church’s structural unity, due to the ecclesiological deficits of the autocephaly (mainly advanced in the 19th and 20th centuries as a result of, and in relation to, modernity), the most essential area of ecclesiology, at least the Orthodox one, is a reconsideration of the necessity of primacy on theological grounds.

Paul Valliere

Paul Valliere: What questions do I consider to be the most relevant and essential in the area of ecclesiology? First of all I would say the question of the participation of the laity in the life of the Church. While this topic is not new in our time, it has not received enough attention in my opinion, especially in the Orthodox Church and some of the other “catholic” traditions. Second, I think the question of how the Church makes decisions about controversial subjects is a crucial question. In Orthodoxy and other “catholic” traditions this question involves the status and the role of church councils. Hence I think that the study of conciliar practice in the Church, both historically and in the present, is much needed. Third, missiology: how should the Church best pursue its mission to the world in our time? This, too, is a crucial question.

Fr Georgy Kochetkov

Fr Georgy Kochetkov: We should always remember that ecclesiology as a separate field of study is a relatively new phenomenon, which arose toward the end of the 19th c. when Lutherans, other Protestants, Orthodox and Roman Catholics all started pursuing study of the church. It is not that the church never took an interest in herself, of course – just think of the relevant portion of the Creed, for instance, and its interpretation. But ecclesiology as an separate field of study didn’t really exist before the late 19th c.

And then the 20th c. was extremely productive in that regard, thanks to progress in philosophy, philosophical anthropology and the study of the Holy Spirit – pneumatology. Then ecclesiology really came into its own. There are several names we could mention in particular: Archbishop Ilarion (Troitsky), then I would say Fr Sergei Bulgakov and Nikolay Aleksandrovich Berdyaev, and then, using the foundation established by these men, Fr Nikolay Afanasiev, followed by Fr Alexander Schmemann and several others.

Experience came to show that the 20th c. was an inherent breaking point, when we ran straight up against the problem of the basis for the Constantinian period in church history, along with its very specific form of ecclesiology. The 20th c. demonstrated that several different ecclesiologies are appropriate to various different periods within history, and that in no way is it possible to fall back only upon the ecclesiology of St Cyprian of Carthage, which was never fully and completely accepted by the church, and which is now often used only by fundamentalists – heretics within the church.

In the 20th c. we saw that different ecclesiologies are appropriate to different periods, and we need to do something about this. The most pressing problem has to do with the boundaries of the Church. The are also questions relating to specific types of ecclesiology: what exactly is territorial/geographic parish or diocese-based ecclesiology on the one hand, and eucharistic ecclesiology on the other? And what is clerical ecclesiology? Or community-brotherhood ecclesiology? It turns out that answers to these questions aren’t simple to come by, not to mention that there are all sorts of mixed and intermediate forms of these basic “types” of ecclesiology. This field is underdeveloped and is of critical practical interest, as well as being of academic, historical and spiritual interest.

And now, when we have every reason to believe that Constantinian ecclesiology is on the wane or has perhaps even seen the end of its day, to what sort of ecclesiology do we turn at this point? What type would be appropriate to our contemporary, secular world? How should the church position itself? What should we be emphasizing? What must change, and what must we keep within our living tradition? These are questions of the most important and most difficult sort, and we must get busy working on them.

The next block of questions consists of the following: What is the role of hierarchy in the church? What is church hierarchy? Is the understanding given us in say, the Corpus Areopagiticum, sufficient? Is the link between the church and heavenly hierarchy found there sufficient, or is it just the opinion of an unknown author? Is it possible to recover the most ancient understandings of church hierarchy, as they became generally accepted in the church? Is it possible to see the Church through the lens of any other different perceptions of church hierarchy? Can we interpret church hierarchy differently, in not such an external and Old Testament fashion as is prevalent now and usually has been throughout history, but in a more New Testament, internal and spiritual fashion? It is clear that if we speak about hierarchy then we must also speak of so-called “laypeople” – how are we to relate to them? Is it necessary to continue separating the church into clerics and lay people or do we have to build internal relations in some other way? This is a second, enormous block of questions of the most important sort, directly related to ecclesiology.

And the third block to which I would draw your attention – is church-state relations. How should we position the church in relation to the state, state structures and agencies which make up the real world in which we live in our country and in other countries? To what extent can or should the church be dependent upon or independent from the state? And to this block we can add questions relating to the church and society and culture.

The last thing – though this is probably a subset of the question regarding church boundaries – is our relations with other churches. It isn’t possible to get away from this – it remains an underdeveloped area of work and a not-fully-understood question in our Orthodox Christian teaching on the church.

These are the things that I consider to be the most pressing questions, and it seems to me incredibly important to work on these main questions, and then turn to lesser related questions, of which there are also very many.

Fr John Behr

Fr John Behr: The modern ecclesiology is tending to be Eucharistic ecclesiology: “where the Eucharist is celebrated there is the church” and so on. I spoke a lot in my interview (at the International Theological and Research Conference “Eucharistic Ecclesiology Today: How We Perceive, Apply And Develop It” – ed.) about the historical circumstances under which it developed and its limitations.

There’s so much more to the church than we’ve come to discuss in our modern ecclesiology. Think, for instance, of the quotation about the church from the martyrdom of Blandina: “The Virgin Mother giving birth to children”. How many times did you hear ecclesiologists speaking about the church as Mother? Actually never in modern ecclesiology, so there’s a whole “element” which is missing! And I think if we were to explore all that “more”, we might find answers which would be unsuspected: the images of Virgin Mother speaking about the church, which are not in mind at the moment.

Dirk Moldenhauer

Dirk Moldenhauer: The main question is how deep our personal faith and love for Christ are. When Christ is in the centre of the assembly, this is a path toward loving one another in a small group and in the entire assembly of the church.

People come into the church when someone calls them in, personally. I think that this is central: people come one after another, when they meet with and manifest trust, and this trust makes it possible for them to share their faith and help each other. In such a case a person feels that Christians are “for” them and “stand behind” them – they want to help me grow as a person – and faith becomes very attractive. We help people who have this sort of trust consciously prepare for a life of living by faith.

Petros Vassiliadis: Certainly we need a new form of being a Church in the new post-Constantinian (and in fact multi-religious, multicultural and even post-Christian) era of globalization. Unless we accept and pursue an encounter with modernity (and post-modernity) at a long term we lose any contact with the world. The Church exists for the world, as the Holy and Great Council has recently reconfirmed, and not for herself.

Paul Valliere: I would certainly say that the Chuch now lives in a post-Constantinian world. Do we also live in a post-Christian world? This is not the same question, and in my view the answer is more complicated: a yes and a no. So perhaps the best way to reply to your inquiry is to say that the issue of what we mean by “a post-Christian world” itself needs much more investigation and discussion.

Fr Georgy Kochetkov: Of course, as I already said, this is one of the most important tasks of Christian ecclesiology. We need to discuss these questions and find the optimal form of church life in this, our post-Constantinian period. Additional questions can arise here. What is the “thousand-year kingdom” of Christ? How does it relate to the church? How is it related to the Kingdom of Heaven? And, by the way, how is the church related to the Kingdom of Heaven? Can we say they are the same thing, or not? In other words, there is a block of eschatological questions, and our age is an age of eschatological problems, so it is hardly coincidence that these questions are now coming to the fore.

In our times, some answers are even found in negative experience. There are some things that we sense very keenly as insufficiencies or distortions of the church in our world and in our time. And through negatives – “no that’s not possible, that is really bad” – we can begin to discern a positive path – “what would be better? What would work in this case?” Life has shown us a great deal – especially in the 20th c. in the period of strict repression of the church during the Soviet era. And the church of that period discovered a lot about her possibilities, to which we find testimony in not a small number of prayers, memoires and other texts about life during those times. So material we have – we just need to do our homework.

Fr John Behr: By studying history properly we are freed to go into unknown future. So, the Constantine era, which started in the 4th c., is over, but if we study the early period, it’s very different. And if it could be different then, it can be different again. It’s not in my hands, it’s in the Lord’s hands how he wants it to be, but we don’t have to be worried about it. But by studying the tradition we find resources we never even knew, even those which are familiar to us from St Ignatius. With ecclesiology people always say Ignatius says, “where the bishop is, there is the church”. He doesn’t say that. He says: “where the bishop is, let the people be present”, just as “where Jesus Christ is, there is the church”. So when we shorten it to “where the bishop is, there is the church”, we’re missing the people and we’re missing Jesus.

Dirk Moldenhauer: In modern Germany and in Western Europe in general, when people hear something they generally ask, “What does that mean in practice?” It’s only after answering that question that they want to know the truth. When they feel that it is possible to live the Christian life then they begin to come closer and ask themselves, “is this thing applicable in my daily life?” If the answer is “yes”, then I’m ready to start to understand. Is the world that bears Christ’s name “possible” today? Is it possible for that world to be present in my heart? And what is necessary for that, if so? For instance, a man has a lot of problems, and when someone prays for him and he sees that this helps, then he’ll say, “there’s the path to God.”

We always need to keep this personal dimension in mind. In a small group, it is possible to pray and to see the fruit of this prayer in personal friendship and faith and to be persuaded that these things are very applicable to life. When keeping such society, people will be ready to hear more.

Our YMCA association has a group of 150 volunteers. Every week they get together in small groups for different meetings – for church services, in house-church groups for fellowship, prayer, common meals, scripture reading and to discuss problems, and in groups which perform various services. Twice a year all 150 of us come together. This meshes people together in and with Christ. When we live in this way the hope of God is in our hearts, and we can share it with our neighbours and our colleagues.