An Orthodox Knight from a Memling painting

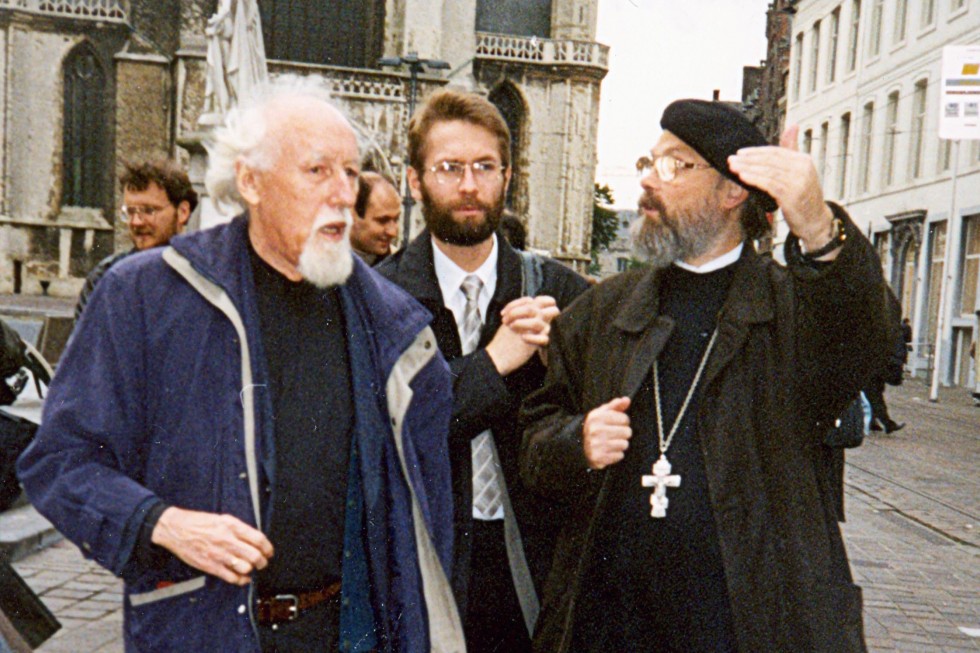

Fr. Ignace Peckstadt, Dmitry Gasak, Fr. Georgy Kochetkov. Ghent, 2002

“First you cannot believe that such people exist, and then you cannot believe that they are gone.” That was the reaction of my friend Xenia, when we learned of Fr. Ignace’s death. We were lucky enough to visit him last summer during a trip to Belgium with Zoya Dashevskaya, the Dean of SFI’s School of Theology. She always called Fr. Ignace a ‘knight’ and strongly insisted that we come to Ghent.

The Beguines’ Quarters in Ghent. We reached St. Andrew’s Church via Black Cat Street

It was here, in 1973, where the successful lawyer, inspired through his contact with Russian emigres to be ordained an Orthodox priest, rented space for his parish in a 17th century stone building, which had once been owned by Beguines (pious lay women who lived near a monastery) and later by the Order of the Rosicrucians. Today, the parish founded by Fr. Ignace is one of the oldest in Belgium and is known far beyond the borders of the country. Its current rector, Archpriest Dominique Verbeke (Fr. Ignace's son-in-law) and his wife Martine received us very cordially and invited us to dinner at their house after Vespers. Overnight they put us up in their guest room just above the church, in the house that once belonged to the Rosicrucians.

The entrance to the building where Fr. Ignace founded his parish

Fr. Dominique tells us how it all began

The parish of St. Andrew the Apostle has, from the very outset, worshiped in Flemish, which helped attract a whole range of very different people and has made the parish a unique spiritual centre in western Europe. In traditionally Catholic and Protestant countries, Orthodox parishes of different jurisdictions are often made up of people who group together based on national principle – either Romanian, Greek, or Russian, etc. Worship is in the given language of the diaspora and hence, the life of the parish may lose an important dimension if communication is reduced to cultural and national grounds and has an inward focus. Therefore, the interest in worship in the local language (in this case, Flemish) and, general attention to liturgical issues such as the intelligibility and meaningfulness of prayer, indicate a certain understanding of Christianity not as a cultural or national trait, a religious background for life or ancestral heritage, but as a particular way of life which is open to any person. And, of course, this is the Gospel understanding of our faith. This doesn’t imply either contempt for national and cultural particularities or an attempt to avoid taking responsibility for the national church; more likely the opposite is true.

Fr. Ignace actively participated in the activities of the Orthodox Fraternity in western Europe, which was for many years headed by the well-known French theologian Olivier Clément. One of the Fraternity’s objectives was to unite Orthodox Christians of different nationalities and ecclesiastical jurisdictions and to support communication and spiritual unity between them. It is notable that in his aspiration to Christian unity, Fr. Ignace always put the preaching of Christ itself and a fully Christian life at the centre, as he understood that these, rather than any external or jurisdictional consideration, are what truly bring people together.

It is thanks to the Orthodox Fraternity of Western Europe that our Transfiguration Fellowship’s spiritual father, Fr. Georgy Kochetkov, who is also the Rector of St. Philaret’s Institute, was introduced to Fr. Ignace.

Remembering Fr. Ignace, Fr. Georgy commented that he “was an outstanding and remarkable personality, who could not help but excite respect simply by how he lived, what he did and how he did it.” “Of course what comes to mind initially is his nobility and chivalry, his selflessness and sacrifice, his delicate moderation and, at the same time, his generosity in fellowship. He received guests at his home and at his parish, and always did all that was needed for pilgrims and parishioners alike. Of course he did this in a ‘western’ style, sparingly, in a concentrated way, without fuss, with dignity. He could really be an example for any westerner. He was a perfect modern westerner; many westerners these days are quite different from that ideal. In this respect, he and his wife Mitta were always an example.

His life’s work was to embody the Orthodox faith in the context of the modern West, both internally and externally. He was a man of western origin, totally western as regards culture, life style and roots. To him, it was of pivotal importance to attain to the synthesis of Ecumenical Christianity – in each separate person, in each separate parish, in his country of Belgium and in each separate diocese. To him, Orthodoxy was an extremely personal and even intimate affair –not intimate in terms of being hidden, but in the sense that he treated it tenderly and very deeply. He was very active and never absent when something significant was happening. If, at any point, a full bus arrived at a Russian Student Christian Movement congress or the Orthodox Fraternity of Western Europe, it was a safe bet that these were Fr. Ignace’s parishioners. There are many Orthodox parishes in Western Europe, but none of them is like his. It was truly one of the centers of that part of the Orthodox church which came into being in Central and Western Europe, primarily as a result of the efforts of the first wave of the Russian emigration.”

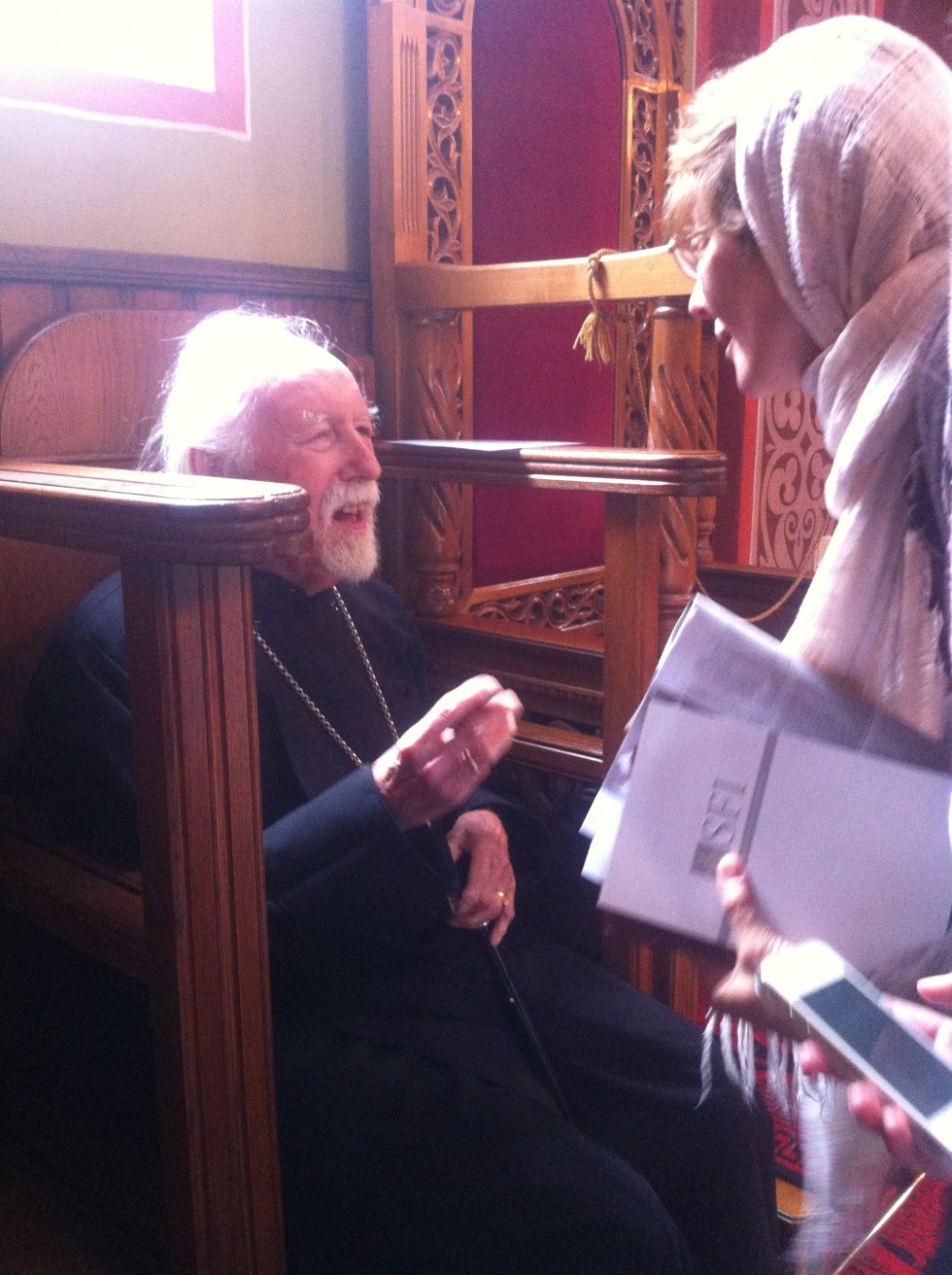

On the day when we saw 89-year-old Fr. Ignace in Ghent, he and his wife Mitta were brought to liturgy from the neighboring town of Eeklo by their daughter Martine. Martine told us that her parents still strive not to miss liturgy. We passed greetings from Fr. Georgy to Fr. Ignace; the last time they met was when the Meeting of the Lord Brotherhood visited Belgium in 2002. We also presented him with a couple of books, including a collection of Orthodox liturgical translations into Russian. Fr. Ignace asked us to sign these as a gift from Fr. Georgy and – in his weak but joyful voice – spoke the following words into our dictophone: “Dear Father Georgy, I always remember our common meetings and some moments in particular. We pray and ask God to bless your Brotherhood and the Russian Orthodox Church and hope that we will meet at the Holy Liturgy every day.”

Archpriest Ignace Peckstadt and Zoya Dashevskaya, Dean of SFI’s School of Theology

Mother Mitta finding pictures of the church of the Dormition of the Theotokos in Pechatniki, where Fr. Georgy served in the 1990s, in Fr. Ignace’s photo album

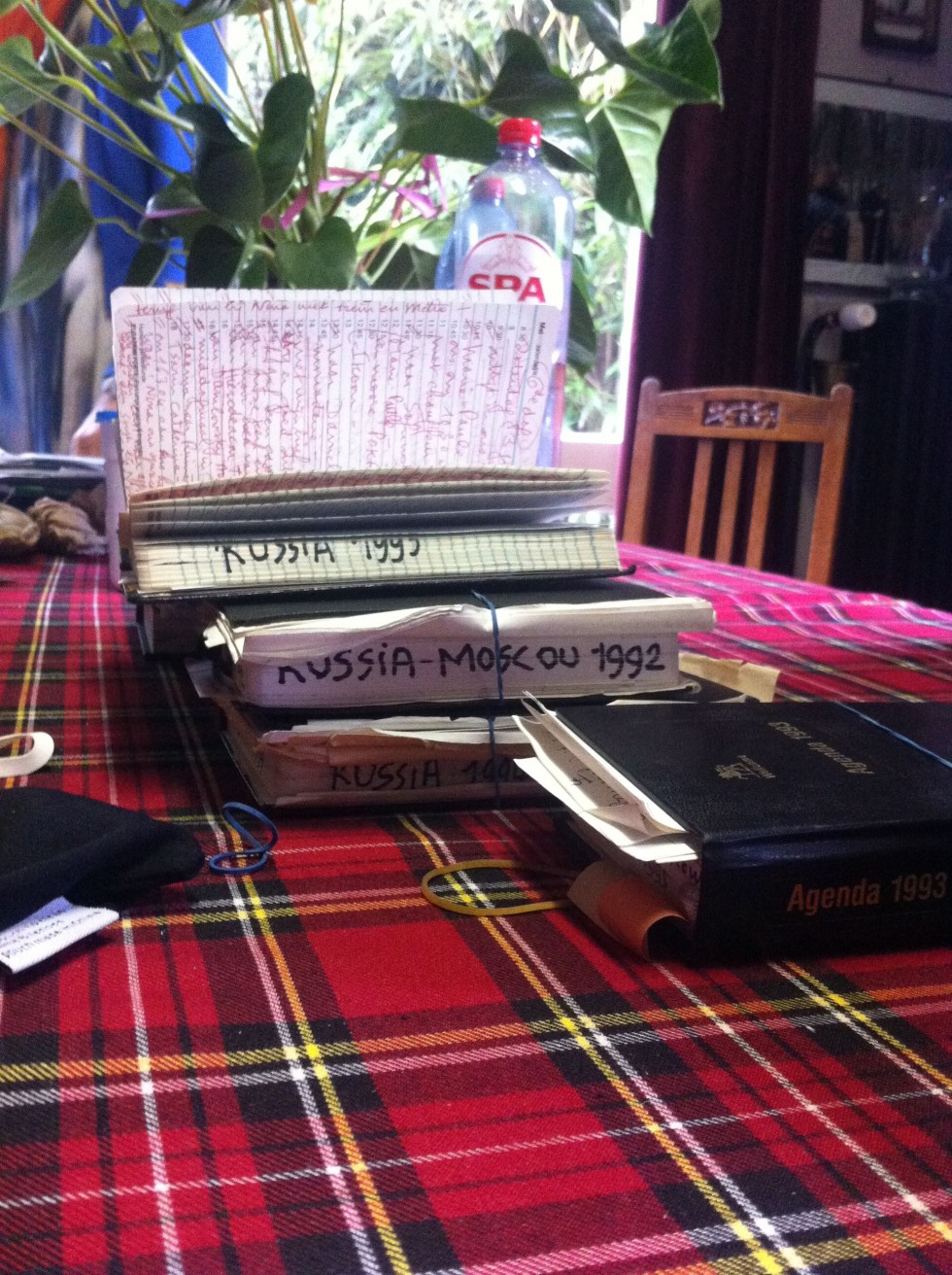

Fr. Ignace’s notebooks

After the liturgy, Fr. Ignace invited us to his home. His wife Mitta served us coffee. Fr. Ignace was resting next to us on the sofa, cloaked in a blanket that his wife had tenderly placed over him. Mother Mitta brought us huge stacks of his diaries and photo albums. We sat in a bright room and looked through Fr. Ignace’s notes about various events in his life, about the great variety of people with whom he had met. To the extent that our knowledge of German and French allowed, we read his impressions and observations. Mother Mitta found the entries about his meetings with Fr. Georgy and some photos taken during Fr. Ignace’s trips to Moscow.

At Fr. Ignace’s and Mother Mitta’s house. In the centre – their daughter Martine. 26 July, 2015

Their house in Eeklo is midway between Ghent and Bruges, and Fr. Georgy has said that this is no coincidence, as they live half way between the Ghent Altarpiece and the Memling Museum in Bruges – for “in Fr. Ignace there is something of the remarkable images painted by the brothers Van Eyck, as well as something of Hans Memling”.

Hans Memling. St. Christopher. The central part of the triptych, the altar of the chapel in St. Jacob’s Church, Bruges. 1484

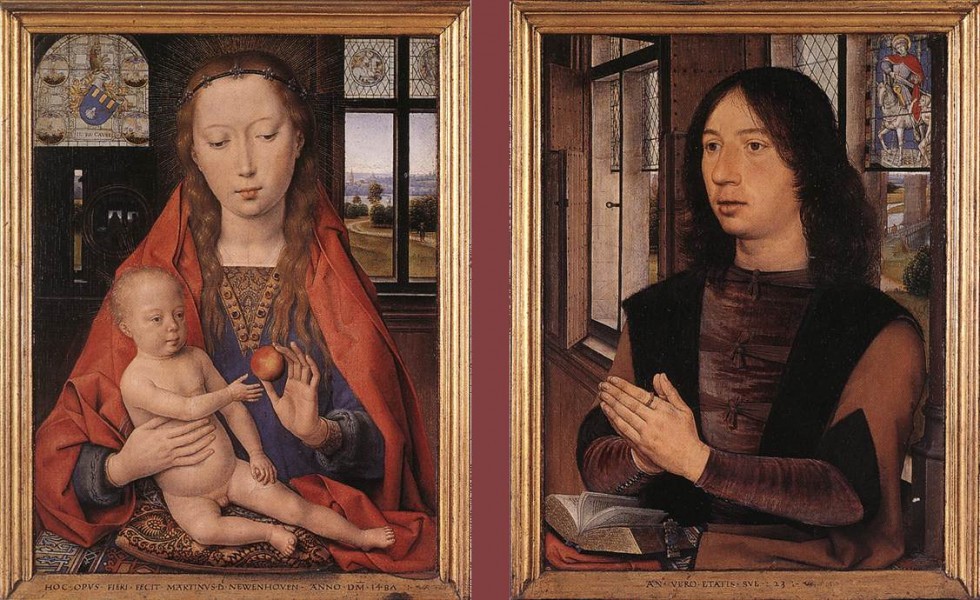

Hans Memling. Diptych of Maarten van Nieuwenhove. St. John’sHospital, Bruges. 1487