The “Laboratory” of Russia’s Future

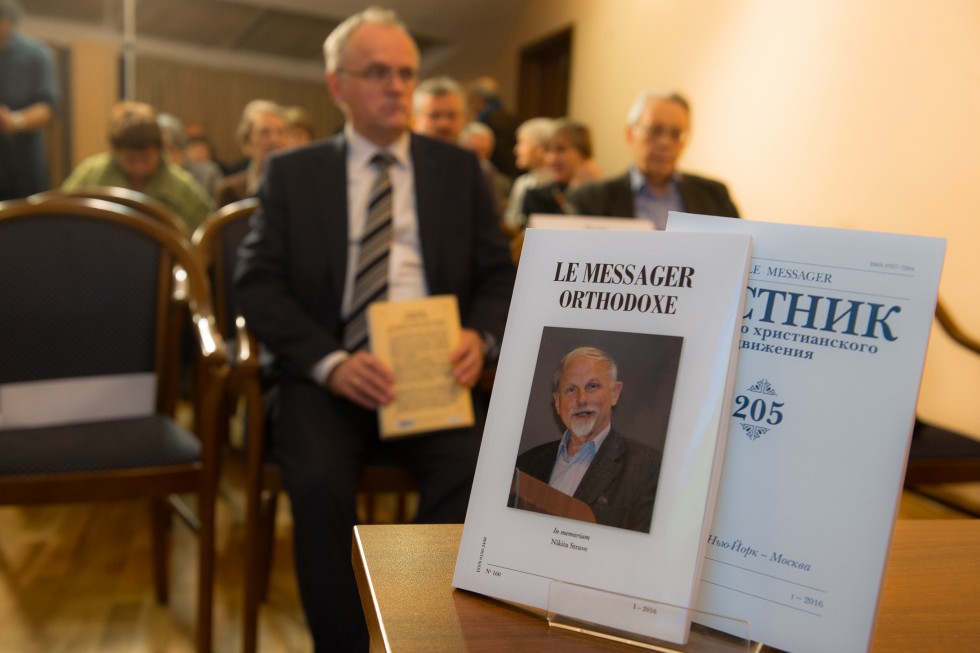

On the 22nd of December at the Alexander Solzhenitsyn House of the Russian Emigration, an evening in the honour of the Journal and its editor was held, in loving memory of Nikita Struve. During the course of the evening, the 205th issue of this, the oldest Orthodox journal of the Russian Emigration, and the last issue produced with Nikita Alekseevich Struve’s participation, was presented. Struve served as the Journal’s editor-in-chief from 1955 until his death on the 7th of May, 2016. Discussions focused on the past, present and future of the Journal.

He was a man of the revival movement

As Nikita Alekseevich wrote in 1973 in a main feature article, “the Journal has already outgrown its role as an intra-organizational news bulletin, although it was specifically this setting within a movement that provided it with momentum and stimulated its growth. When the door into Russia was barely open, the principles of our movement turned out to be more timely and necessary than ever before… More than anything, I refer to the belief in the absolute truth of Christ’s revelation and its appearance in the Church. The movement sees the Church not only a treasure chest, not only something holy, but as the creative power which is called to transform the world.”

It is precisely this faith that made possible the Journal’s traditional approach of publishing literary, theological and political-societal materials in a single journal. “Christian spiritualism and an approach which separates ‘the truth of the church from the truth of history and life’ is foreign to our movement”, said Struve.

In Stuve’s columns from the editor, it is possible to discern something of an “editor’s programme for the Journal”, which is exactly what Natalia Likvintseva, a Senior Researcher for the House of the Russian Emigration and new editorial secretary for the Journal has done. She reviewed the main feature articles of the journal over the years, in which Nikita Alekseevich’s loyalty to the Church and to Christ’s revelation come together in a touching way in his love for Russia, with his “confession of her incorruptible face – God’s vision of her, which abides despite her lapses.”

In 1969, Nikita Alekseevich wrote that, “The goal of our journal is to bear witness to the true Russia. This is not a political goal, but a spiritual and moral one. Deep reality is inseparable from factual truth. Continuing the tradition of Orthodox theologizing by revealing the wealth of Russian culture, to thoroughly study the religious and intellectual movements of the West, and to pay close attention to and further the spiritual renewal of Russia – these, in short hand, are the Herculean tasks that stand before the our journal.”

Fragments from an Interview with Nikita Struve

“The liveliest and best part of the emigration understood itself to be Russia’s witnesses to the West, as Mother Maria Skobtsova called it, a ‘Laboratory for Russia’s Future’, because it was only possible to act within a very limited space and with practically no resources,” said Struve, in one interview. And, through the person of its Editor-in-Chief, an inheritor of “the best part of the Emigration”, the journal was exactly such a “Laboratory for Russia’s Future”.

Tatiana Viktorova, who worked as editorial secretary alongside Nikita Struve for 17 years and who is now taking over the position of editor-in-chief, explains that all of the Journal’s principles were things that Struve carefully tried to embody in life: “He was an activist. For him, maintaining the link with the Russian Christian Student Movement was a continuation of that same spirit of Pentecost of the Russian Emigration, which formed a focus of discussion at the first Congress of the RCSM and about which Fr Sergei Bulgakov spoke in such an enlightened and eloquent manner… For me, associating and interacting in relationship with him was the embodiment of freedom in the church. I both saw and felt the degree to which it is possible to live this freedom and pass it on to others. Already at a later date, when living in Paris, I came to understand how difficult it sometimes is to embody this freedom – even in the supposedly-more-free Parisian setting.

Tatiana Viktorova – new Editor-in-Chief of the Journal of the Russian Christian Movement

A whole group of people shared their memories of Nikita Struve, including: Professor Alexander Kopirovsky of St. Philaret’s Institute, Lev Mnukhin, Specialist in Literature and the Russian Emigration, Journalist Sergei Chapnin, Specialist in Art History Irina Yazykova, Poet Dmitrij Strotsev, and other guests. Publisist and Commentator for the Journal Science and Religion (Nauka i Religia), Valentin Nikitin, sent a poem, written on the occasion of the 40th day after Nikita Struve’s repose.

Fr Georgy Kochetkov, Rector of St Philaret’s Institute, and Poet Olga Sedakova, sent their greetings to the participants of the event.

“This journal is a great instance of the spirit of faith in our Church and in our nation… and a witness to the highest quality of Christian thought and culture,” said Fr Georgy in his message to the assembled crowd. “The Journal, for us, is forever connected with the name of Nikita Struve, who to this day is its guardian angel. It was not by happenstance that Nikita Struve dedicated his entire life to the service of the Russian Church and Culture, wishing to bring them out onto the world stage and make them the property of all. Nikita Alekseevich did all he could to preserve the sparkling white ornaments of the Russian Church, so as not to lose anything of the achievements of Russian culture during the 20th century. This was a great achievement indeed – a great podvig – which should never be forgotten by future generations, whether in this country or amongst the inheritors of the emigration.”

Olga Sedakova noted the unparalleled level of culture and of the publications in the Journal, the freedom and level of responsibility of what was written by the authors and the publishers: “Given many circumstances, it is now only in the Journal that many topics can be discussed, and I don’t mean timely-political topics, but rather exactly the opposite – the most general, deepest themes for Orthodoxy and for Christianity. Theological material has more or less disappeared from domestic-published Russian journals. Subject matter connected with the relationship between secular and church culture is discussed at an unacceptably primitive level. The link with modern, European Christian thought – both Catholic and Protestant – simply remains unestablished. About all this and much more it is possible to write in the Journal, given its free and open position of goodwill, which the Journal has chosen for itself since the very beginning.”

Alexander Kopirovsky

“Of course, knowing a person as unique as Nikita Alekseevich is a gift of God, and one wishes to be nourished by interaction with him, said Aleksander Kopirovsky. Nevertheless, in his every appearance and action – quick, joyful, fiery, humourous and free – he dismantled our impression of himself as someone completely unique. He never emphasized the distance between himself and the person he was relating to and gave to each the inspiration to rise above himself.”

Sergei Chapnin

“Nikita Alekseevich was a happy man: 20th c. Russian culture, the culture of the emigration – that was his circle of friends,” said Sergei Chapnin. “For him, it was unbelievably easy to the Journal’s editor. Today it is difficult for the editors. Today we suffer the paucity of our language – the language with which we have spoken about the church for the last 25 years. And in some way hope is connected with the language of the emigration, because the language of Metropolitan Anthony and Fr Alexander Shmemenn isn’t apoor language.”

The poet and publisher of Metropolitan Anthony’s heritage, Dmitry Strotsev, called those people, which were revealed to the Russian reader on the pages of the Journal “bearers of an elfin principle” within Christianity: “There is some sort of a gnome-like principle – heavy and underground, and yet at the same time so light and calling us to somewhere, to somewhere that we really do want to go. Metropolitan Anthony, Mother Maria Skobtsova – and all of them bearing an amazing similarity to each other! Berdayev, Bulgakov – they are all so bright – the strongest of people – though they found themselves in amazingly cramped conditions, they stood out from and above their environment… and began to think about youth and to form a new Christianity which came straight out of their catastrophically tragic experience. And the first thing they gave their thought to was freedom itself.”

Remembering how in the beginning of the 1990’s Nikita Struve brought a whole truckload of books to Russia, Dmitry Strotsev posed a question: “Why wasn’t the experience of the Movement imported along with this truckload? Perhaps today we should consider how this experience – so incredible and elfin – is represented not only by the Journal?”

Tatiana Viktorova

“Nikita Alekseevich was already in the hospital, and it was already obvious that he required a heart operation through which he was unlikely to live,” said Tatiana Viktorova, recalling her last meeting with Nikita Struve. “But when I came to him with the printout of the 205th issue, he was alive with unusual inspiration. We planned the 206th and 207th issues, and spoke about new trips to Russia and new publishing projects of the “Russian Way” publishing house. In his thoughts he was, as ever, in Russia.”

Struve worked on the main feature article for the 205th issue up until his last days. The article focused on relationship between contemporary government structures and the Orthodox Church. “Nikita Alekseevich put particular emphasis on the degree to which the inheritance of the emigration is not taken up in modern Russia. In particular he expressed absolute lack of understanding in the return to and growth of respect for Stalin,” said Tatiana Victorova, in presenting the 205th issue to the assembled crowd.

The recurrent theme of the 206th issue of the Journal, which is due for publication in January, is the creative work of Mandelstam, whose birthday coincided with Nikita Struve’s. The 207th issue will touch on the theme of the Local Council of 1917-1918. In particular, Tatiana Victorova spoke of an article dedicated to his critique of the Council by the historian Viktor Alexandrov, a specialist in the heritage of Fr Nikolay Afanasiev.

The majority of back issues of the Journal can be found on the site of “Russian Way.”