A Pilgrimage to a Land Across the Sea

Our pilgrimage group was led by Fr. Georgy Kochetkov, the Rector of St. Philaret’s Institute and spiritual father of our Transfiguration Brotherhood. The last time that Fr. Georgy was in Cyprus was twenty years ago at the General Assembly of Syndesmos – the World Fellowship of Orthodox Youth. The rest of us were coming to Cyprus for the first time.

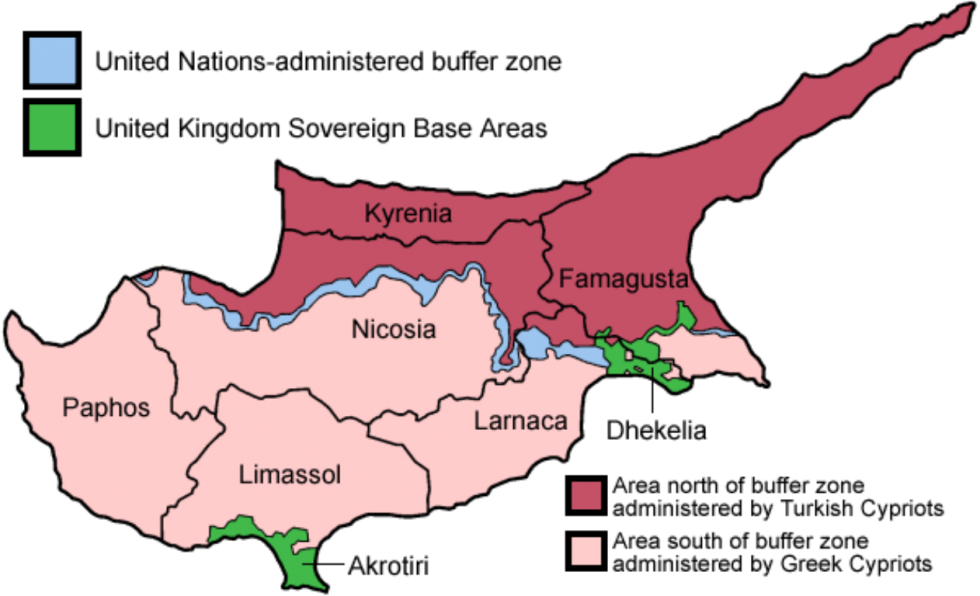

We stayed on Queen Elizabeth Street in the village of Akrotiri, which is a suburb of Limassol. Our home was a small, two-storey cottage, overlooking a parched salt lake.

Cyprus is a former British colony. Here one can see triple sockets and cars driving on the left side of the road. Our suburb turned out to be located next to a British military base, which meant there were bombers flying overhead every day, and English soldiers revelling loudly on the nearby streets at night. We had come to one of the so-called British overseas territories. These are special lands under the sovereignty of her Majesty, which nevertheless are not part of the United Kingdom. At least we saw no border guards. More than half of the local population are military families and subjects of the British Crown.

Before the British took Cyprus, it was conquered by Assyrians, Egyptians, Persians, Alexander the Great and finally by the Romans. In the middle ages, the island was owned by the Arabs (7th century), Crusaders (from the 12th century), the Venetians (15th century) and the Turks (16th century). In the 19th century, the Cypriots tried to break free of the Ottoman yoke, but this attempt led to cruel persecution of the Christian population. Ottoman rule ended only in 1878, when the island was sold to the British, who announced in 1925 that it was their colony. In 1960, Cyprus gained independence. Archbishop Makarios III, the head of the church, became President of the republic (in the Church of Cyprus, the title of Archbishop is superior to the title of Metropolitan). Less than fifteen years later, however, the northern part of the island was occupied by Turkish troops. Today this is the self-proclaimed Turkish Republic of Northern Cyprus, which is recognized only by Turkey and separated from the Republic of Cyprus by a buffer strip controlled by UN forces. The presence of peacekeeping troops on the island is quite visible: at the airport, one is treated to a cordial greeting by men and women with machine guns slung over their shoulders.

Outside of various atavisms of the colonial past, such as the village in which we were staying, today the southern part of Cyprus is an independent state. In its territory there is the autocephalous local Orthodox church, and the majority of citizens identify themselves as Orthodox Cypriot. No illusions, however; as in most Orthodox countries, Orthodoxy here is more just part of the national culture.

Nevertheless, when on the very first day of our visit the owners of our little cottage learned that we were Orthodox faithful, they very kindly brought us an icon of St. George. And – quite without reference to our religion – they treated us to delicious homemade pies each evening for dinner: one day it would be a rich pie with olives, another day an Orange cake or brioche with halloumi cheese.

We bought our food in a supermarket with the optimistic name “Catastrophe”

A Cradle of Human Communal Living

Man has apparently inhabited the island of Cyprus for more than a quarter of the forty thousand years that scholars estimate have passed since the advent of our brother, the Cro-Magnon man. The first local settlements date from nine to eleven thousand years ago. We were even lucky enough to visit one such village, called Khirokitia.

It seems that our ancestors were not creatures entirely aloof from spiritual matters, and that even back at that time they sought to commune and live together, driven not only by utilitarian interests. They buried their dead under the floor of their dwellings. They were also, apparently, rather skilful at building: we saw one Neolithic wall which was similar to a residence from today with many entrance halls – and it is still standing today. It occurred to us that in those times there might have been a primitive householders society.

Here we also saw the pods mentioned in the parable of the prodigal’s son. There is nothing very special about them – they look like giant beans but grow on trees. Fr. Georgy gave us his blessing to taste them, but somehow we found we had no appetite for them.

These are the nutritious pods

And this is a fig tree

In Cyprus there are many ancient floor tile mosaics. Entire cities have stood the test of time. We visited two large archaeological sites – Kourion in the south, and Kato Paphos in the west. The foundations of municipal and residential buildings remain almost entirely uncorrupted and should in no way be called ‘ruins’. It is probable that one of these houses belonged to the proconsul who, according to the book of Acts, converted after hearing St. Paul preach the Gospel.

In Kato Paphos we were particularly impressed with the floor of the huge temple of Apollo, which had at one time been located here; there were detailed mosaics and an altar for sacrificial offerings, surrounded by hunting scenes. Perhaps before meeting the Apostle Paul, the Roman official might have worshipped the gods here, but his life was turned upside down by the Apostle’s words that the “God who made the world and everything in it is the Lord of heaven and earth and does not live in temples built by human hands.” How relevant the Apostle’s sermon would be for contemporary Christians who primarily associate the Church with temples, altars and donations!

In the Temple of Apollo in Kato Paphos

We have to admit, though, that there are some church buildings without which the image of our historic church would simply be incomplete.

The Church of the Righteous Lazarus, which dates from the early 10th century, is one of three Byzantine churches in Cyprus. It is believed that the tomb of Lazarus, the friend of Jesus Christ whom our Lord raised from the dead, was located in Larnaca. According to the tradition, Lazarus was the first bishop of Cyprus. Although this is likely just a pious legend, we sang the troparion to the Righteous Lazarus and one of the Sunday troparia with great inspiration inside the church. For us, “Lazarus of the four days” is the image of the Church which dies and is raised in history.

In the village of Kiti, not far from Larnaca, the 6th century church of the Panagia Angeloktisti has been preserved for us. In 1952 during this temple’s restoration, a mosaic depicting the Virgin Mary with the Child in her arms, surrounded by the Archangels Michael and Gabriel was discovered under the plaster in its apse; it is from this mosaic that the church gets its name. In the 11th century, the basilica was transformed into a cross-domed temple. Two hundred years later, a chapel, which is now used as the entrance to the main church building, was added.

A mosaic in the apse of the Panagia of Angeloktisti Temple. 6th century

A giant olive tree or something of that ilk is growing right next to the temple. The tree is protected by the state. Its spreading crown is supported by special gardening stakes. To us it seemed like this tree is one possible image of true Christian brotherhood.

In the mountain village of Lagudera, we visited the church of the Panagia tou Araka, which is a UNESCO World Heritage Site. This church was built in 1192, and the exact date is known because the church was erected immediately following the conquest of Cyprus by Richard the Lionhearted. Here there are unique 12th century frescoes which are perfectly preserved apart from some of the faces which were damaged by the Turks. These frescoes are the work of Theodore the Truthful, who is also responsible for painting the cave church at the monastery of St. Neophyte, which we also managed to visit.

To save the frescos, mountain churches in Cyprus are protected in special sarcophaguses. You can only take photos from outside

The interior of the Church of the Panagia tou Araka. Photography is prohibited inside, so this photo was taken from the site icons.spbda.ru

The 12th-century fresco in the cave monastery of St. Neophyte depicts his ascension. We immediately realised he was a very humble man

In Nicosia, the capital of Cyprus, which is divided into Greek and Turkish sectors, we visited the Byzantine Museum which is a project of the Archbishop Makarios III Foundation. The museum is exhibiting some remarkable icons from the 12th – 14th centuries; some of the later icons are also interesting, although they more resemble folk art. Some of the icons reflect western influence. Others, conversely, are similar to Serbian and even Russian icons. The museum also has wonderful frescos dating from the 14th and 15th centuries and Byzantine mosaics from the 5th – 6th centuries,found and removed from their original sites in Northern Cyprus and illegally sold by the Turks to private collectors in the United States and Europe. Later, by court decision, these pieces were transferred back to Cyprus and to the Museum.

In Limassol Cathedral

Meeting People

Our itinerary also included the Byzantine Museum in Paphos. We planned to visit it in the morning, before going to the Temple of Apollo. But on that day Chrysostomos II, Archbishop of Nova Justiniana and all Cyprus, arrived in the city, and museum curator Metropolitan George of Paphos was called away with all his staff to meet the Archbishop. Our itinerary was instantly transformed when, at the closed doors of the museum, we met two Russian couples from St. Petersburg and Yasenevo. Yulia, who was a tourist from St. Petersburg, proved to be an expert in folklore and sang “Christ is risen” (the Paschal Troparian) to us in Bryansk-style chant. For our part we sang her the same troparion in Russian (rather than Slavonic) and in Greek. Fr. Georgy was very inspired by the conversation. He said that the Lord had shown us that meeting with living people is more valuable than contemplating icons and mosaics.

In general this year we enjoyed a lot of communication – more than ever: with each other, with the local people, and with brothers and sisters from Russia who had come to Cyprus at the same time as we did either by accident or by design. This communication was the most important part of our pilgrimage.

On Sunday, we were at liturgy in the Russian-speaking parish of Christ the Lover of Mankind, which is served by a young priest called Fr. Georgy Vidyakin.

The day before we left, Fr. Georgy Kochetkov was interviewed by the radio station of the Holy Metropolis of Limassol, and the interview is due to be aired in the coming days. In the evening that same day at the invitation of a charity called “Oriyentir” (Landmark), SFI Associate Professor of Church History Yulia Balakshina, delivered an open lecture in Limassol on the topic of her doctoral thesis – dialogue between the Church and secular culture. She outlined the history of this dialogue in Russia in the 19th and 20th centuries based on examples of the relationship between the church and the world of literature, which became an issue ofnational significance. The spiritual authority of Russian writers often competed with the very authority of the church. Yulia expounded upon about the grounds of this dialogue, beginning with the Christian genealogy of the Russian language, which is the ‘basic material’ of literature itself. She also spoke about the main points of tension and the stages of development in this relationship between the church and literature in Russia. After the lecture, there was a conversation on the present state of this dialogue and whether the dialogue itself has any current prospects.

Yulia Balakshina delivering her presentation in Limassol – an open lecture on “The Dialogue between the Church and Secular Culture: History and Modernity”

Meeting Holy Scripture

A tradition has developed during the course of our travels over the last few years – each morning and evening, immediately after prayers, we discuss the New Testament passages we have just read in the wonderful translation of Archimandrite Yannuarius (Ivliyev).

Thoughtfully reading Scripture is another context in which we meet the Church. Ultimately, the New Testament texts are one of the few sources on the life and faith of the early Christians. We try to understand the meaning of what is written without either simplifying or ironing out difficulties, without skipping obscure passages and/or contradictions within the text, and without detaching from either the historical context or our own experience of life in the church. It is always interesting to ponder the tradition we are inheriting, the way in which it evolved in history, and which spiritual emphases the church made at different stages in its life.

In our previous pilgrimages to Armenia and Georgia we read the epistles to Timothy, Titus and Philemon. This year we read the epistles to the Ephesians and Colossians. In the letter to the Ephesians we discovered the experience of a community taught by a prophet who was probably a younger contemporary and close disciple of the Apostle Paul.

Based upon patristic and other interpretations, but above all on the text of Holy Scripture itself, Fr. Georgy commented, line by line. Armed with the Greek text, we tried to refresh our memory of everything we were taught at SFI. To help confirm or to reject our hypotheses, we also made reference to scholarly commentary. Sometimes our evening discussions lasted well beyond midnight, and our morning discussions were usually interrupted by our Cypriot driver, Pampus, who would drive up and wait for us in the bus right at the doorstep of our house.

In a week and a half, we travelled to nearly every corner of the island of Cyprus and even managed to get in some swimming in the sea. Fr. Georgy’s assistant, Sergey, practiced his English in endless conversations with Pampus, relating to him the meaning of biblical psalms, Russian folk song and even lyrical songs, which he heard us singing during the trip. Apparently we didn’t sing that badly, because he seemed to gain a certain trust in us. On the last day of our trip, after unloading our luggage at the airport, Pampus took Fr. Georgy aside and asked him to hear his confession.

Returning to Domodedovo Airport, there is almost always a strange feeling that you have just left yesterday, and it was the same this time, too. But there was something else that gave the lie to this feeling – we were back at home yet we were different and somehow happier than when we left, because of the riches of having experienced a true meeting.