Khomyakov – an Amateur Theologian of Great Value

“Alexey Stepanovich Khomyakov: Philosopher, Theologian and Poet” was the theme of the conference. In the article below, conference organizers and participants Dmitry Gasak, Yulia Balakshina and Elena Nepoklonova, share their thoughts on the first Russian theologian.

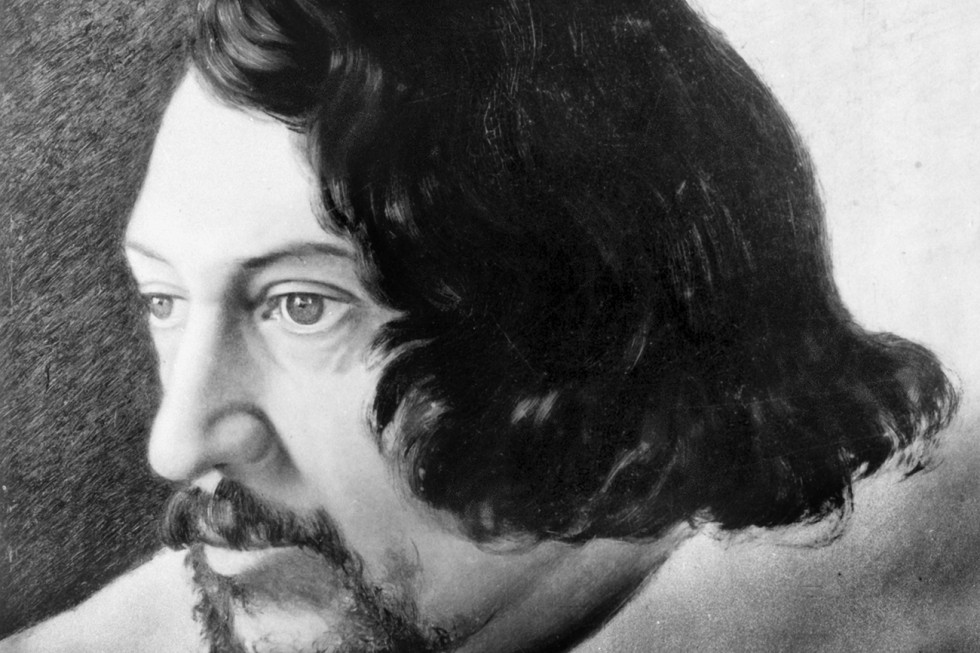

A Portrait of Poet Aleksey Khomyakov. State Historical Museum. Reproduction. Mikhail Uspensky/RIA Novosti

At the end of the 19th c., Nikolay Aksakov, in his polemical work “Don’t put out the Spirit!”, insisted on the right of lay people – unencumbered by seminary education, holy orders or by being on the payroll of a “centralized religious organization” – to teach in church. Along with other “voluntary profits” whom Aksakov defended, such as Dostoyevsky and Vladimir Soloviev, is the officer and poet, Alexey Khomyakov.

It is the right and the responsibility of every person not simply to “come to the clergy for the teaching they hand out, being happy to submit to their ‘healthy influence’”, but to “search for religious truth in his or her own right.” In his book, Aksakov speaks many times of “work in the spirit in one’s own right”, moreover he speaks of the spirit as if it is a muscle well-known to us all, the exercise and contraction of which supports the true life of the human person. In Khomyakov, that muscle worked impeccably well.

“Poet, Mechanic and Philologist, Doctor, Painter and Theologian”

This is the way Historian and Diplomat, Dmitry Sverbeev – a personal friend – described Alexey Khomyakov, noting the great breadth of his friend’s various talents.

“Khomyakov was a notable phenomenon because he spoke as a leading theologian who was original in his thought. As a person he was fairly distant from official church circles, though in the character of his life, his worldview and the way he arranged his day-to-day affairs, he was deeply a person of the church,” explains Yulia Balakshina, PhD and senior lecturer at SFI and the Herzen State Pedogogical Institute. Berdayev calls the first free-thinking Russian theologian “that Russian landowner – practical, down-to-business, a hunter, technically-handy, a dog-lover and homeopath.” “I allow myself, in many instances, not to agree with the so-called opinion of the Church,” Khomyakov admits in a letter to Ivan Aksakov. “The so-called opinion of the Church”, which was often just the personal opinion of particular hierarchs, seemed to him to be “not of the Church.”

Alexskey Stepanovich Khomyakov. Self Portrait, 1842

That being said, this freedom-loving polemicist caused confusion among his contemporaries with his obvious commitment to the Orthodox Church. “He was a reverent observer of the fasts, went to church, took communion – for him these things were not just some sort of intellectual baggage, but the experience of his real life”, says Balakshina. “He comes across as a chaste person, who didn’t want to parade his emotions, who could keep the private treasures of his life in the depths of his heart. His fate and the early loss of his wife, who was so close and dear to him, and how he lived through this loss, tell us that there was deep faith in his heart. Herzen, when he lost a child, raised a revolt against the cosmos itself; Khomyakov lives through his personal tragedy in a very different way, although he was far from being a white-bread mama’s boy! Rather, he is remembered as an ardent opponent in animated discussion with a good sense of humor, ready to spend a whole night battling for his values and convictions.”

“Khomyakov is cut from a single mass,

formed precisely out of granite”

A deep religiosity that he got from his mother in his childhood years, combined in Khomyakov with his ability to think freely and make discernments on almost any topic, and with an openness that was ahead of his time, which allowed him to consider opinions, as well as philosophical and theological constructs and ideas which were quite foreign to him.

Alexey Khomyakov was not considered a serious figure of the official theological academy of science, and his theological works were published first in the West. “Although his views are seriously in conflict with Roman Catholic or Protestant views, his freedom of thought and his openness to discussion very much impressed western Christians. Sometimes it still seems to me as if he is studied more in the West than in the East,” said Dmitry Gasak, Vice-Rector of SFI and teacher of Ecclesiology (Christian teaching on the Church).

“His theological letters were not only a topic of research interest – they were a living voice which caused others to want to understand Orthodox Christianity better, and sometimes to be received into the church, as happened with Protestant Theologian William Palmer, who was received into the church with nearly his entire congregation,” reports Elena Nepoklonova, PhD and Khomyakov researcher.

The “One, Holy”: The View from within

His main theological thought was about the Church, and he approached his topic, as Berdayev notes, “from within, and not from without.” “For Khomyakov, the Church is not an object of theological thought, but life, in which he took part to the utmost,” says Dmitry Gasak, clarifying, that the discipline of the freedom-loving Khomyakov, and his observance of church rules and participation in church ritual, issued from a desire not to separate himself from the church in any way. For him, faith in God was unthinkable without faith in the church. He tried to take full responsibility for the church, not separating himself from her in any way, though he was part of a secular societal class, and many of his close friends were not nearly so strict in their observance of church rules.”

“…always had his eyes open to everything,

never closing them to anyone,

was never dismissive about anything, and never prevaricated to himself or cut corners with his consciousness…”

Berdayev wrote that, “Khomyakov is cut from a single mass, formed precisely out of granite. He is unusually integrated, precisely delimited, manly, faithful and always fully awake.” “This integrity characterized his view of the world around him, of life, the structure of church and society, his household, and the position of Russia within the larger world,” says Dmitry Gasak. He combined, in himself, both responsiveness to the whole world and faithfulness – to his people, his country, his culture and his faith – in all their various aspects. And this has great significance for us today, insofar as it is particularly these traits which we lack.”

Elena Nepoklonova also notes the integral and non-objectified character of Khomyakov’s theological thoughts, when compared to those of his contemporaries: “He tried to describe spiritual phenomena in the language of the world, adjusting them to rational categories. He starts from the perspective of revelation – the Gospel itself – and from there he builds his religious thinking. A modern theologian simply can’t get on at all without Khomyakov’s conceptual constructs, especially as regards ecclesiology – Khomyakov’s teaching on the church – which he based on a description of her attributes.”

Bogucharovo – The Museum-Estate of Alexsey Stepanovich Khomyakov

The main attribute is sobornost. Although the term sobornost doesn’t belong to Khomyakov personally, it is he, who first endeavored to understand what this particular attribute of the church – which is spoken of in the Creed – means. “Not long ago I ran into an answer given by well-known Fr. Georgy Mitrofanov, to the question of how to understand sobornost. He said, practically with indignation, that some officer who had barely any theological training had given a undecipherable and incoherent answer to this question which isn’t based in any particular theological tradition, and that for a century and a half since, people have been trying to understand what in the world he meant. It seems to me that this perspective is rigorous in the extreme,” says Yulia Balakshina. “In this is the very paradox of Russian thought – that it arose not as the result of systematic, scholastic theological knowledge, but from the experience of real life and faith, fellowship, and perhaps from the experience of close circles of friends. Such was Khomyakov’s thought, and this is undoubtedly its value, rather than some sort of shortcoming.”

“The Writer of Prose must Suppress the Writer of Verse”

His contemporaries were amazed by the perfect culture of logical reasoning which Khomyakov demonstrated. “Very few were able to dispute at his level,” says Nepoklonova. “His perfect logical reasoning joined together with poetic inspiration, his ability to understand poetry and compose verse, himself. His poems were highly regarded by Pushkin, Vyazemsky and Venevitinov.”

But though this was the case, Khomyakov himself evaluated his poetic compositions quite humbly: “Without false humility, I know of myself that my poems, when good, hold to a certain type of thought; in other words, the writer of prose everywhere swallows up and it follows, must ultimately suppress, the writer of verse.”

On 12 October 1826, Pushkin, who had recently returned from exile, gave a reading of his drama Boris Godunov at the home of Dmintry Venevitinov, on Krivokolenniy pereulok, in Moscow. “On the next day,” recalls M.P. Pogodin, “a reading of Yermak, which Khomyakov had just brought from Paris, was planned. Khomyakov didn’t want to read and we didn’t want to listen, but Pushkin insisted. Khomyakov sacrified himself at the altar with his reading.” Pushkin was at the height of his ascendency. The failure of Yermak was somehow programmed…*

“When Khomyakov spoke about himself as a poet, he did not mean to say anything about his professional identity”, says Dmitry Gasak. “Probably he was more referring to the way he related to life as a whole. Poetry was in vogue and, moreover, poets had a certain dignity and a kind of inner right to judge life – to say their piece. It seems to me that in this his sense, his conscious definition of himself as a poet had a sort of prophetic sense about it. This is expressed not only in his verse, which was for him, a sort of form. It is expressed also in his letters, his theology, his life, and in his attitude toward management of affairs and to questions of societal, political and historic import – for instance in his attitude toward the question of freeing the serfs.

“He saw societal relations as akin, in some way, to the way in which people within the church relate as members of a divine-human reality,” says Nepoklonova. “It is no wonder that he gave so much attention to thought about the Russian rural parish.”

Khomyakov’s Hardest Thought

Amongst the Slavophiles, Khomyakov bore a leadership role. He is considered the head of the school of thought and its first theologian. Yuri Samarin, who humbly considered himself Khomyakov’s student and follower, wrote that Khomyakov “lived in church” and “was for us an entirely original phenomenon of completely free thinking religious consciousness. He always had his eyes open to everything, never closing them to anyone, was never dismissive about anything, and never prevaricated to himself or cut corners with his consciousness. He was completely free – that is to say, entirely true to his convictions, and he demanded the same freedom and right to be true to their convictions for others, too.”

To allot the Church with authority

is an act of freedom, faith and consciencefor every Christian,

and not the affair of the institutional church

or of those who are ordained

One of Khomyakov’s hardest thoughts is that “The Church is not an authority.” This is the way Samarin explains it: “I confess, submit and resign myself – so in fact, I don’t have faith. The Church offers only faith, calling faith out of the heart of man and won’t be satisfied with anything else. In other words, the Church only takes free people under her wings. He who brings his service of a slave to the Church, not believing in her, is neither in the Church nor of the Church.” To allot the Church with authority is an act of freedom, faith and conscience for every Christian, and not the affair of the institutional church or of those who are ordained.

Khomyakov saw the Church “not as a doctrine, not as a system and not as an institution,” but as “a living organism of truth and love.” His best-know work, entitled, The Church is One begins with the words, “The Church is not a multitude of people in their personal particularity, but the unity of God’s mercy, alive in this multitude of reasonable creatures, who resign themselves to this mercy.”

Perhaps it is even harder for us to understand Khomyakov’s thought than it was for his contemporaries. On the one hand, “The Church is not an authority”, which is to say that the Church, in the sense that it is Church, doesn’t presuppose reliance on any external organizational principle. On the other hand, nor does the sense of Church underscore that Church is some sort of a unity. For the post-Soviet consciousness, any mention of unity congers up thoughts of the kolkhoz. The phrase “collective church conscience” says very little to us, though we know well what party conscience is. When we hear the words, “multitude of reasonable creatures, who resign themselves to mercy,” it sounds rather abstract, though it sometimes seems as if the 20th c. was specially designed to demonstrate the meaning of a multitude of insane creatures, consolidated by a mutual guarantee of denouncements and murders, and subject to fear, lies and repression by brute force.

Apparently it was necessary to live through the 20th c. and experience what lack of conscience is, so that Khomyakov’s thought might become necessary to us, though perhaps all the lack of conscience we’ve lived through makes things even harder for us. A very bold assertion stands behind Khomyakov’s intuition of sobornost and his sophisticated interpretation of the Church as a free and internal unity of God’s creatures. This assertion is that unity must be founded not only upon the “right to disgrace”, but also in “work in the Spirit, in one’s own right.” This unity is dependent not only upon fear and external force, but also upon internal freedom. Several decades later, Berdyaev calls sobornost a “quality of the personal conscience standing before God.” And another question, though perhaps not the only one, is whether we wish to obtain to this quality today.

“for many people

the question of our self-identity

finds its focus in our Soviet experience;

this is a catastrophe for our people”

Let’s Talk about Khomyakov

The revelation of the Church’s sobornost which came through Khomyakov still needs to be heard and received within the Orthodox Church. One of the stepping stones along that path was a conference run by SFI, the Philosophy Department of Moscow State University, and the Tula Historical Architectural Museum, which took place on the 5th of October, 2017 – the day we remember Alexey Stepanovich.

The conference organizers believe that it is important not only for those of us within the church to return to Khomyakov’s heritage as we work on our own self-knowledge. For the Russian people and the country as a whole, it is important to return to Khomyakov’s heritage as we consider our self-identity. “The break in our cultural tradition is so severe that for many people the question of our self-identity finds its focus in our Soviet experience; this is a catastrophe for our people,” said Dmitry Gasak. “For this reason, the experience of people like Khomyakov and the early Slavophiles is of particular value for us.”

“At this point, Khomyakov has been accepted by church circles, and in the published Social Concept of the ROC one often finds citations of one or another of his assertions,” says Yulia Balakshina. “However in preparing for the conference it was quite difficult work trying to find anyone who could speak specifically about Khamyakov’s theological heritage. We are ready to accept him as an historian, a philosopher, or even a poet – but to make sense of and fully express what he might have done as a theologian, doesn’t come easily.”

“We very much wanted to attract the attention of the leadership of the Tula Region, and perhaps the Russian Ministry of Culture, to the poor condition of the Khomyakov estate, which, miraculously, is still standing,” said Dmitry Gasak. “Many of our conference participants, amongst whom are some very well-known and distinguished people, supported this initiative and wanted, with their participation, to draw attention to that wonderful estate.”

The house in which Alexsey Stepanovich Khomyakov lived

As of today, the church and bell tower on the estate are intact. The house itself is in poor condition – only two or three rooms belong to the museum. People live in some of the other rooms and, until not long ago, still others were occupied by a post office. The facades were restored not long ago, but again are already falling apart. “As is always the case with such things, the museum is supported only by the enthusiasm of its employees,” said Gasak, “and we would like to support them.”

“Of course we didn’t organize this conference to focus on the past,” he said. “The second portion of the conference was a round table discussion entitled, ‘Is it time to Slavophilocize?’ What is the priority for us today as we try to understand the spiritual, theological, philosophical, societal, political and nationalist aspects of Slavophile thought? For Khomyakov it was important to ‘question the spirit of life.’ We, too, would like to discuss what the ‘spirit of life’ is calling us to in our day and age.”

Source: Stol Media Project

___________________

* Koshelev V.A., Pushkin and Khomyakov // Кошелев В. А. Пушкин и Хомяков // The Pushkin Commission Chronicles / USSR Academy of Sciences Subdivision for Literature and Language. Pushkin. Comission. – L.: Science. Leningrad. division, 1987. – Volume. 21. С. 24-40.